A different kind of writing project

at the mercy of the pen

The Lady Sei Shōnagon was a member of the Imperial Court in Heian Era Kyōto, and she attended on the Empress Consort Teishi for over ten years, beginning in the 990s, CE.

When not at court, however, Sei Shōnagon wrote her thoughts down in a series of essays that, in 1002 CE, was published as 枕草子 (makura no sōshi), The Pillow Book.

The essays within the book are stylistically unique, described structurally as 随筆 (zuihitsu), which I have chosen to translate as at the mercy of the writing brush. She wrote whatever came to mind—writing as pleasure.

The zuihitsu format is new to me, or at least the name is. One of my instructors during the Kenyon Online Winter Writing Workshop, Dinty W. Moore of Brevity magazine fame, described it to me. I tested the format in a class assignment. After reading from that essay, feedback from my classmates convinced me that a personal color atlas—a collection of zuihitsu essays inspired by Japanese colors—could indeed be my next book.

The idea for writing about Japanese colors or taking inspiration from them was not as recent as last month, though. I have a collection of page-a-day color calendars from the past three years, but the first book on Japanese colors I bought was in the early 2000s, when I was seeking inspiration for the artwork I created using Illustrator, Photoshop, and fractal generation applications like this.

I had originally planned for my next book to be another researched memoir. To chart the history of the marriage equality against my own marriage journey. As I always do, I even had a title in mind: I Will: A Queer Journey to Marriage. But I will come back to that book at another time. The last thing I want to have happen while writing it is for the United States Supreme Court to overturn Obergefell, the 2015 ruling that extended marriage equality to all fifty states.

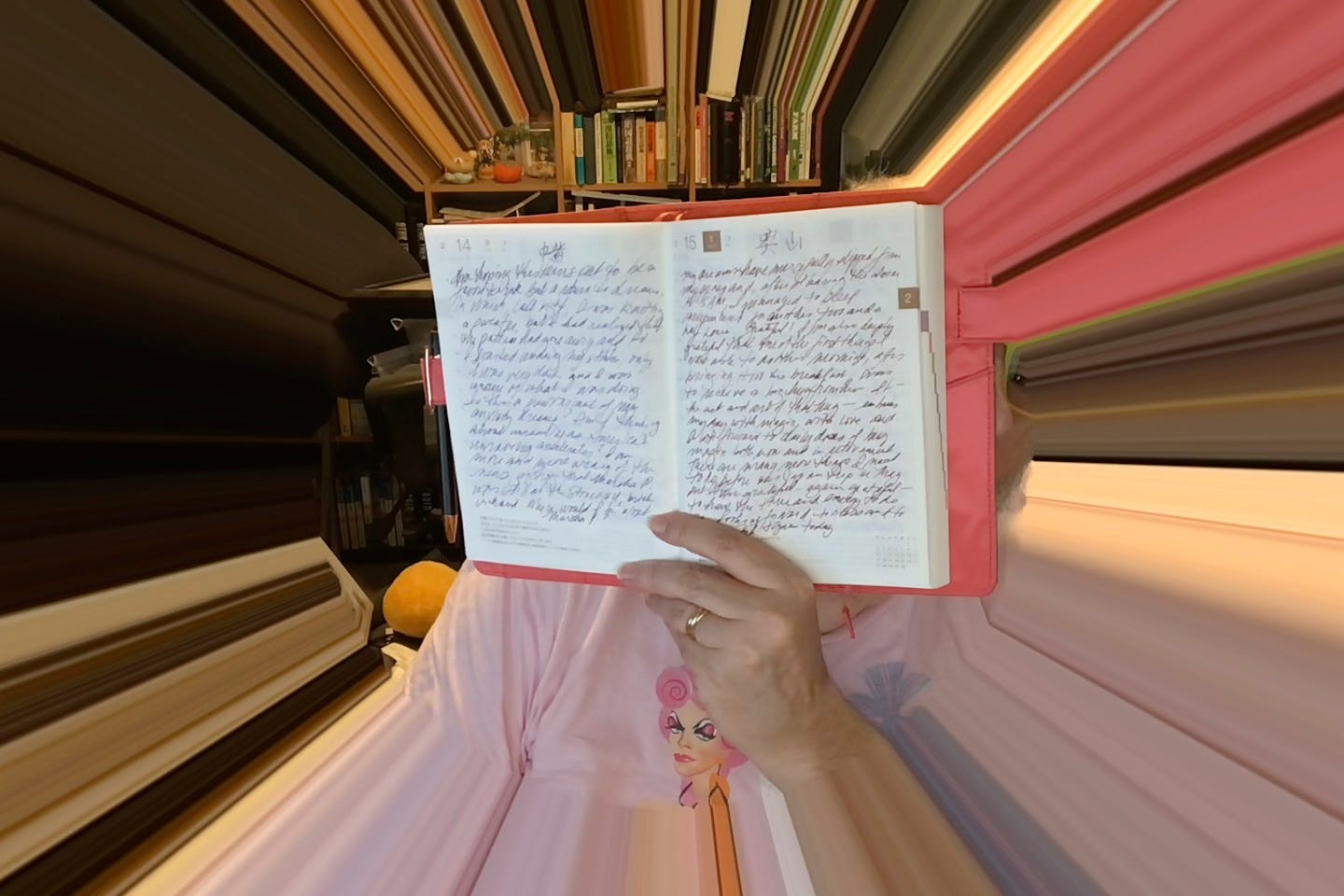

Over the past several weeks, my writing practice has returned to what it was in the fall of 2020, when I began writing Crying in a Foreign Language. I wake up and write. I don’t look at my phone. I sometimes put on the kettle for the day’s preferred caffeine. I sometimes make some toast. But when I get to my desk, I pull out my Hobonichi journal, wash off my glass dip pen, choose a bottle of ink from my collection, and write.

Once the journal page is done and I read through the Hobonichi wisdom at the bottom of the page—I translate yesterday’s quotation from author Naoki Matakichi as:

We all impress ourselves when we’ve thought of one hundred things, but nearly all those thoughts won’t be original. Even so, those thoughts go on to become books. But reading such a book inspires you to think your 101st thought, which might lead you to a conclusion or idea that no one has ever had before. I believe that books are not just for tracing someone else’s thoughts; they are a stepping stone for your next thought.

I then write a zuihitsu essay, sometimes two. Sometimes that day’s color inspires me, but no matter what happens, I give in to my thoughts and let the words flow. Maybe a point will emerge, maybe it won’t, but my fingers submit to my mind. I write about politics, my health, Japan, memories, and Hiro… the only topic I train my mind to avoid is work. As exciting as my nine-to-five is these days, I don’t want to dream of labor, to paraphrase James Baldwin.

And maybe that’s what these increasingly numerous flash-like zuihitsu essays are. The best kind of dreams, free from constraint. You might imagine why I find writing them so engaging, given all else we’re forced to contend with nowadays.

I don’t have any writing news this week, but I hope to have two things to share during the week of March 10th. The agent who has my manuscript is still reading it, and I won’t expect any updates on that front for a while.

I’ll be at AWP Los Angeles at month’s end. If any of my readers will be there, let me know. I’d be honored to share an in-person smile with you.

Love the incorporation of color into your writing. While living in Japan in the 60s and early 70s my mom studied woodblock printing under one of the Japanese masters living in Tokyo at the time. I wish I could remember his name, but he is the one who did the cover work for Mitchner's book that took place in Japan and includes a commentary on a tree growing on the airfield on the Atsugi Naval base. The tree was said to be a prince who was transformed into a tree and that anyone who tried to cut down the tree would die. Everyone who had tried to cut down the tree HAD died under weird circumstances, so the tree stayed, and the airstrip was built around it.

I lived on the airbase and knew of the tree before actually seeing it written about in Mitchner's book, Sayonara. I think the artist was Wantanabe, as my dad has the Noah's Ark print he did hanging in his home.

Wonderful post! And fantastic idea I think it’ll be a great success!