A Queer Holiday

Getting ready to celebrate

17 March 2024

This is an odd thing to say, but I want to write something other than a newsletter today.

I have been heads down in revisions to my memoir during nearly every free moment.

That includes research. I dusted off my copy of Plato’s Symposium to find Aristophanes’ speech. I found a used copy of Gay Histories and Cultures, priced north of $400 on Amazon, for just $11 on eBay. I read through Tony Kushner’s Angels in America once more, looking for a specific line.

That includes polishing existing writing. I finally paid for the premium version of Grammarly, and although most of its suggestions are dismissed because they’d dull the blade of my writing (i.e., I prefer there to be rhythm in my sentences without repeating the same grammatical cadences—and now I’ve gone and mixed metaphors to make a point… sheesh).

This includes writing the missing chapters. That moment during my first year in Japan (in 1989) when the same high school friend I had tried to hypothetically come out to back in 1983 told me he knew all along. That moment in 1996 when I took Hiro to visit the same go-go place in Times Square that I had visited in 1982 (when I was, yes, sixteen). The moment in 1997 when Hiro and I visited Hanauma Bay (on Oahu) and I realized that memories of my ex held no more power over me.

I’ve also been submitting again. An essay on tarot cards has gone to five literary magazines. More excerpts from the memoir have gone out. I have about fifty pending submissions, thirty no-response-so-I-assume-it-is-a-no submissions, and about eighty outright rejections since the beginning of 2022.

But I do have news to share.

Last week, two Japanese courts, the Tōkyō District Court and the Sapporo High Court, both ruled that the Japanese government’s refusal to support marriage equality is in violation of the Japanese Constitution. The Tōkyō ruling posits the violation in Article 14: “All of the people are equal under the law and there shall be no discrimination in political, economic or social relations because of race, creed, sex, social status or family origin.” The Sapporo ruling goes beyond that and adds both paragraphs of Article 24 as well: “Marriage shall be based only on the mutual consent of both sexes and it shall be maintained through mutual cooperation with the equal rights of husband and wife as a basis.

“With regard to choice of spouse, property rights, inheritance, choice of domicile, divorce and other matters pertaining to marriage and the family, laws shall be enacted from the standpoint of individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes.”

Japan remains the only member of the Group of Seven that does not offer marriage equality. These two rulings join earlier rulings from Nagoya and the Sapporo District Court. Every case but one (Ōsaka is the exception) brought to Japanese courts so far has found that not allowing couples like Hiro and me to marry in Japan is unconstitutional. The ruling (and ironically named) Liberal Democratic Party (a party of deep corruption conservatism and lacking in any liberality) has resisted calls from the seventy percent of Japanese citizens who now support marriage equality. Still, Prime Minister Kishida and his party’s popularity continues to weaken as the scandals keep coming and talk of higher taxes abound.

So Hiro and I remain cautiously optimistic that change will come.

One more thing…

In the last issue, I mentioned that Invisible City, the literary magazine of the University of San Francisco, had accepted an excerpt from a chapter in an older revision of my memoir, Privacy. That excerpt is now live.

Content warning: The chapter touches briefly on my frustrated sexuality while living in a Japanese homestay in 1988. I don’t consider the content to be graphic, but some readers might object to mentions of sexual organs.

A reprint

This newsletter is coming up on its second anniversary. I wanted to share one of the earliest issues.

8 April 2022

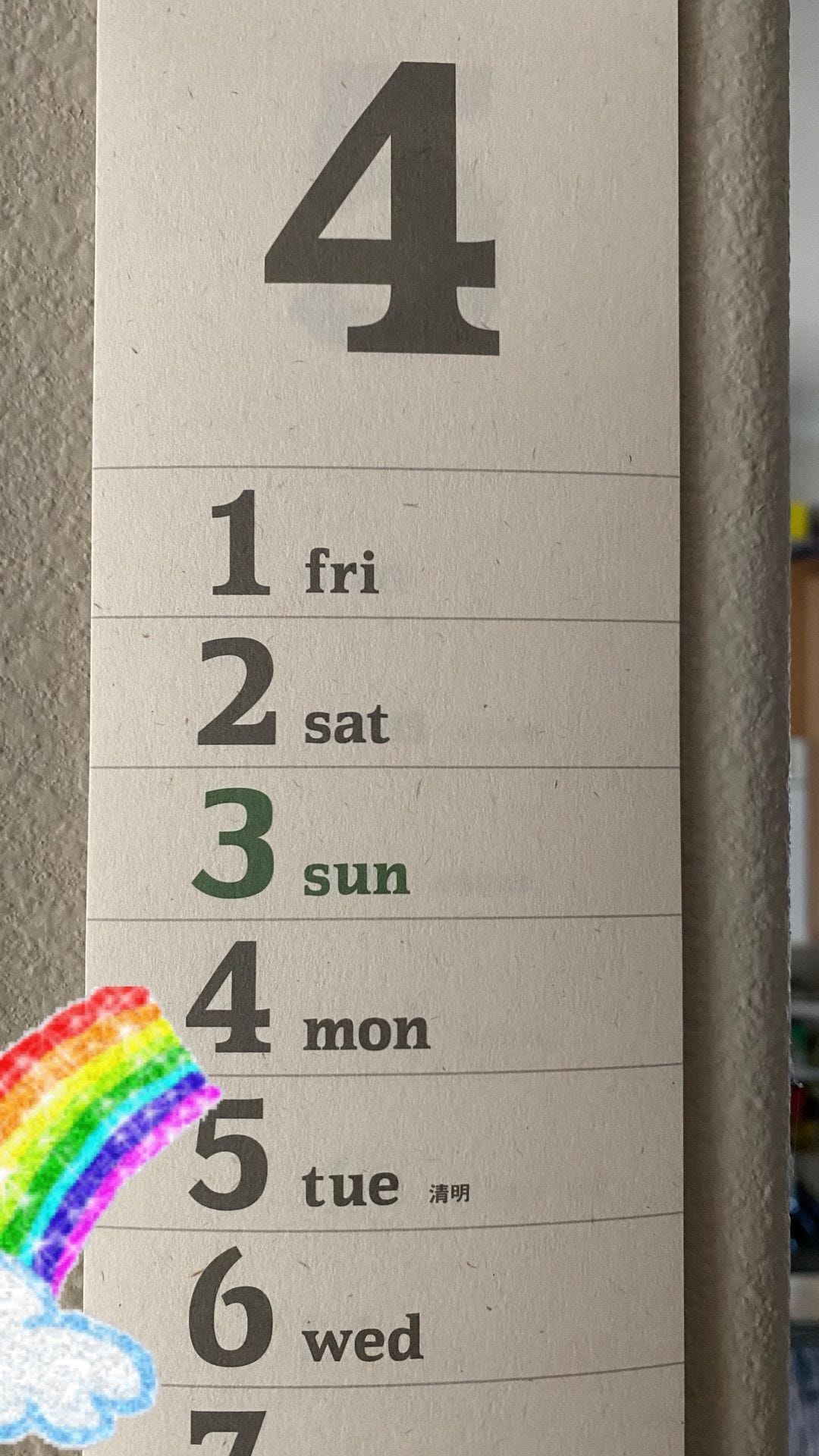

Calendars trigger memories, and Monday of this past week, the fourth day of the fourth month, dredged up a few.

One of the best aspects of my ten years in Japan is the constellation of friends I now have there. Some were more than friends at one point before I met my husband—Hiro refers to them as my fan club, without any jealousy—but that is part of the beauty of queerness. Not only do we live on a wonderful of identities, but we also get to craft a rainbow’s array of relationships.

Anyway, before my prose gets overly purple, let me return to the fourth of April.

Japan once had distinct holidays to celebrate girls and boys. The third day of the third month, 桃の節句 (momo no sekku, the season of peach blossoms), was Girls’ Day, and the traditions live on. Pink, pale green, and white candy, chirashi sushi with rape blossoms, and displays of dolls. (I have a pair, just the Emperor and Empress dolls and not the complete set as shown in the second photo).

.

The fifth day of the fifth month is 端午の節句 (tango no sekku, the season of the first ox—the ancient Japanese calendar was inspired by the Chinese calendar. The fifth month was the ox month, and the fifth day of that month was the first ox day of the month.) was Boys’ Day. During the reforms after the end of WWII, Boys’ Day became a national holiday, now called Children’s Day, and Girls’ Day was relegated to cultural observances only—no holiday. (Don't get me started on misogyny in modern Japan—another newsletter's topic, to be sure.)

I’m guessing you’ve picked up on the pattern here. The third day of the third month, the fifth day of the fifth month… what, then, was the fourth day of the fourth month? If you're guessing it's a reaction against the binary of gender roles, you'd be close!

But here’s where things enter urban legend or apocryphal territory: Wikipedia Japan does not even include an entry on this holiday. Among my rainbow-dwelling Japanese friends, the fourth of April was very unofficially celebrated as オカマの日 (okama no hi, f—t day).

I chose that translation, f—t, for a reason. Regardless of its beginnings in Japanese, the use of the term okama to refer to gay men, or to drag queens, or to members of the trans community is now considered a slur, as the f—t word in English is.

Okama had that power in the 1990s when I lived in Tōkyō, too, but I never had the word punched at me as an insult—one advantage of being nearly two meters tall in a country where the average male height is more than twenty centimeters less than that. Instead, okama marked community. We used it among friends to denote friends, sometimes with the bitter sting that gay men can master, regardless of nationality.

オカマ is a tricky word to tie down etymologically. Several people I knew thought it was related to the homophone, お釜 (okama), the word for a rice cooking pot. I heard many reasons. For example, rice pots have a round bottom, and gay men have round bottoms (my data samples suggest variability in bottom shapes, however). Or, rice pots are as tough as gay men are. Maybe that's true?

The theory that Wikipedia Japan favors dates back to Edo period Japan, when that word, お釜, was slang for a male anus (and I have not yet investigated why that was). By extension, fans of that orifice were referred to by that word as well.

The theory I loved most is one I cannot substantiate, but the way it was related to me was thus:

When Buddhist monks first arrived in Japan from China and Korea in the sixth century CE, the monks brought the teachings of the sutras with them, including the Kama Sutra (カマ経, kama kyō), that amazing testament primarily to ways one can lead a life of fulfilling relationships but also to the creativity of physical love. Adepts of that sutra would have known about sex between males as a result, and that particular teaching and its adherents were referred to with an honorific version of the sutra’s name, 御カマ, okama.

But I must sadly admit that theory is most likely part urban legend, part wishful thinking.

One final note, after a rejoinder to not use オカマ when speaking Japanese, please, is that the word for a woman who prefers the company of gay men (what we used to refer to as a fag hag in English, another term that has rightly become a pejorative) is オコゲ (okoge), which, I am assured, comes from the homophone お焦げ (okoge), the burned bits of rice stuck to the bottom of the お釜. Gay men and straight women, best buddies forever.