A Year to Forget

even though I'll remember it all

A sensation akin to motion sickness has been stalking me since early November. So much, and so much of that bad, has happened in rapid succession. Keeping with the bird metaphors, there have been times I wished I were an ostrich.

Speaking of Nagasaki, a few months ago, a professor of religion at my alma mater, Williams College, reached out with an interesting request. He had some source materials on the persecution of Japanese Catholics in Nagasaki (the Portuguese arrived with Jesuits, including Francis Xavier) at the dawn of the Meiji Era (in the late 1860s and early 1870s) before the Shogunate laws against Catholicism could be nullified. A shout-out to one of my Japanese professors at Williams, now a professor emerita, Yamada-sensei, for letting the professor know I was a translator.

The first piece of material the religion professor asked me to look at was a pre-WWII book (as a PDF) compiled by a Japanese Catholic bishop, documenting the persecutions. There were significant reforms to Japanese orthography after WWII, and I learned to read and write based on those reforms, which covered spelling and character use. A good example is in the picture above. The word for ostrich was written in Chinese characters, kanji, as 駄鳥 at the beginning of the first column of text on the right. To the right of those characters is a pronunciation guide for them: ダテウ. After the reforms, however, those characters were no longer read as dachō but as date’u. The post-reform pronunciation guide for 駄鳥 became ダチョウ (dachō).

Not only did I need to recall the old pronunciations to read the material, but I also needed to learn how words that are now exclusively written in the hiragana script, like これ (kore), were once written in kanji (之), AND I also needed to learn two new (to me but very old-fashioned) writing styles. One, called 候文 (sōrōbun), is an ancient polite form of writing that, among other differences from modern Japanese, replaces the desu and -masu copula forms (a part of speech that marks politeness) with sōrō. And then there were excerpts of official Japanese government documents written in classical Japanese, 古文 (kobun, literally old text), which are predominantly kanji, with a faint scattering of katakana as syntactical marks.

As you might have guessed from reading the preceding paragraphs, I found this translation challenge to be incredibly frustrating (I spent hours looking up old forms of kanji and even had to dust off my 1988 copy (the 27th printing) of Nelson’s The Modern Reader’s Japanese-English Character Dictionary). Fun fact: when I didn’t have lessons to teach or prepare during my first three years in Japan, I read my Nelson’s cover-to-cover, all 1,109 pages, searching for obscure characters. The word for bread in Japanese, パン (pan), comes from the Portuguese, pão. As I wrote it, it’s written nearly exclusively in katakana, the script used most commonly for loan words (like ice cream, アイスクリーム, computer, コンピュータ, and Brian, ブライアン). There are, however, kanji for パン, too: 麵麭. The first character is usually read as men and refers to noodles, like rāmen (拉麺). The second character is read as hō and refers to balls of sticky rice. But together? Bread!

I also found the translation work to be the kind of challenge that lights up all my neurons. I had to learn a lot of new things about Japanese, most of which were so arcane that even Hiro neither knew nor understood it.

The material itself, however, was grim, describing the torture and persecution of people who had managed to hide their illegal faith for centuries, and it was only with the arrival of European Catholic missionaries in the 1850s, as Japan prepared to re-open itself to the world, that brought things to light.

On the morning of December 13th, Japan time, Thursday afternoon my time, a shockwave rippled through the Japanese Twitter accounts I follow.

Seven years ago, on Saint Valentine’s Day, same-sex couples across Japan filed lawsuits, claiming that the lack of marriage equality not only discriminated against them in ways that violated Japan’s Constitution but that the same lack had made their lives more difficult.

Municipal governments throughout Japan have offered varying types of separate but equal solutions, but the lack of national-level recognition remains problematic. Remember, the value of marriage does not lie in the ceremony of marriage. As Hiro and I quickly learned in 2013 after the US v. Windsor decision that invalidated key parts of the Defense of Marriage Act, the married state brings hundreds of civil benefits, everything from hospital visitation rights, to taxes, to Social Security, and, most importantly for us, immigration.

The coordinated strategy the plaintiffs in Japan’s multiple lawsuits followed recognized a key point. Entrenched bureaucratic power, combined with the crony corruption of Japan’s (until late) ruling party, meant that a legislative solution for marriage equality was out of reach. The courts, as had been true in the United States, would offer a more direct road to victory.

But that road included regional courts, appeals to high courts, and, ultimately, an appeal to Japan’s Supreme Court. And for the most part, the plan is paying off.

In 2024, the appeals to three high courts, Sapporo, Tōkyō, and Fukuoka, all resulted in similar rulings: the lack of marriage equality presented unconstitutional harm to the plaintiffs. Sapporo based their verdict on two sections of the Constitution. Article 14, Section 1 guarantees equal treatment under the law, and a lack of marriage equality denies equal treatment. Article 24, Section 2 stipulates that marriage should be entered into freely (which was written to abolish contract marriages) and, according to the Sapporo High Court, should be applied equally to all persons.

The second high court ruling was Tōkyō’s, which used Article 14, Section 1, in its decision for the plaintiffs.

Fukuoka was the third high court to rule, doing so two days ago on December 13. And Fukuoka’s justices brought the heat. Not only was the denial of marriage equality in violation of Article 14, Section 1, and Article 24, Section 2, but it also violated Article 13, which protects the rights of individuals to pursue happiness (a notion enshrined in the US Declaration of Independence but not in our constitution).

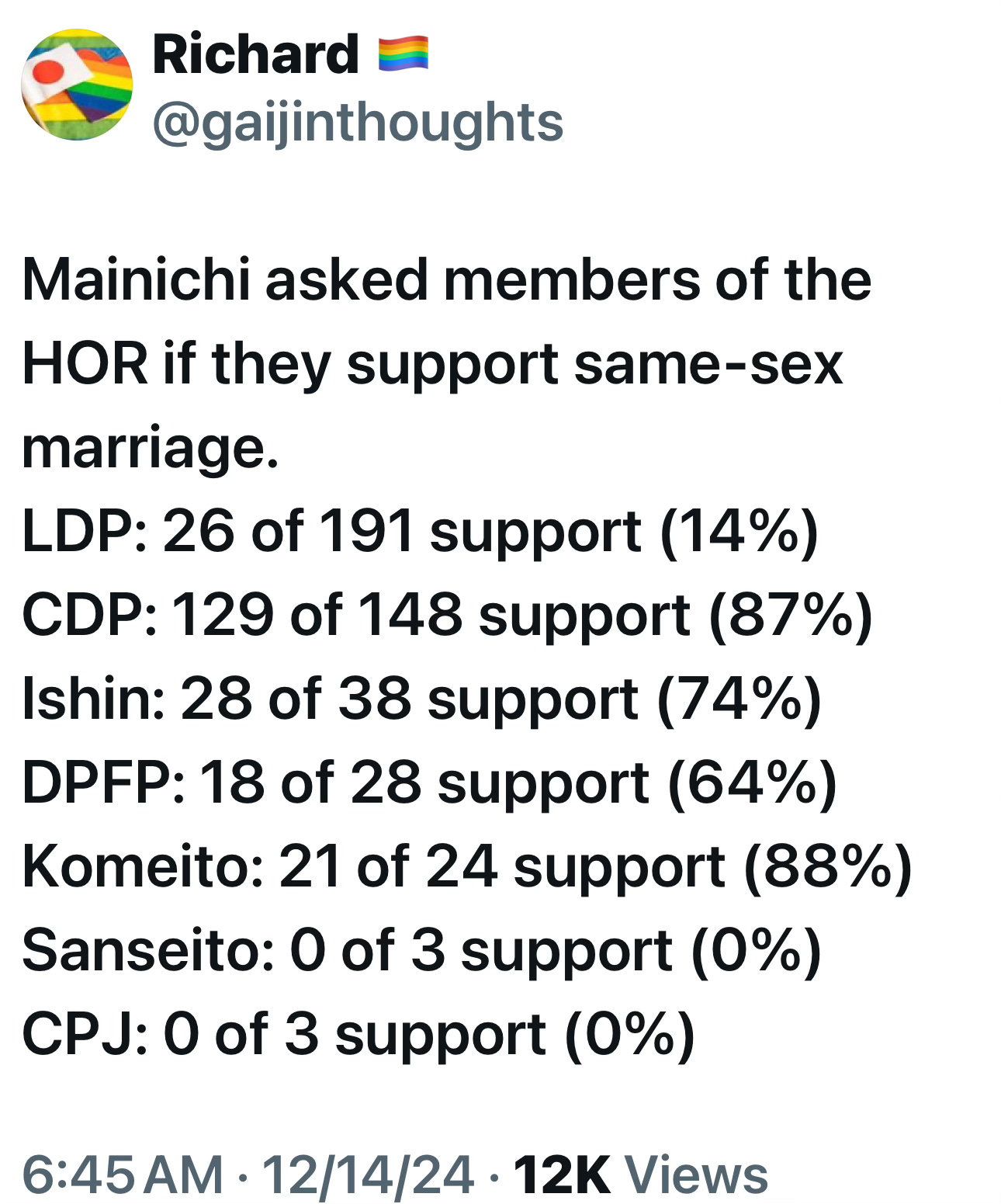

Japan’s House of Representatives is split on a legislative remedy. The majority of pols in the conservative parties, including the once-regnant Liberal Democratic party, are against marriage equality. However, the majority of members of the center, center-left, and progressive parties are in favor, and for the first time in a long time, they outnumber the conservatives.

The next high court ruling will be in Nagoya, early in 2025. The Supreme Court is set to rule on the issue in either late 2025 or early 2026.

Hiro and I have booked our next trip to Japan for roughly two weeks in May of 2025. We’ll bookend our visit with stays in Tōkyō (hotels are booked in Asakusa and Ryōgoku) but the bulk of the time will be spent in the Kyōto area. We’ll be looking at potential retirement homes, but because we’ll have a car, there are some places I want to visit, too.

Mount Hiei, to the northeast of Kyōto City, is home to an incredible complex of Buddhist temples. The Tendai sect of Buddhism was found there in 788CE and given the temple complex’s geographical position, geomancers (practitioners of Feng Shui, a divination rite that arrived in Japan together with Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism) believed the complex could protect Kyōto. The monks there grew powerful, both politically and militarily, as a result.

When Oda Nobunaga, one of the first samurai warlords to unite Japan, began his campaign, he had the temple complex razed in 1571 to prevent the monks from opposing him. (I’m toying with the idea of writing more about Oda—incredibly violent in battle but also, as we would understand it today, a bisexual icon. Sometimes the samurai baddies are queer!)

Shortly after I started writing this long-ass issue of Out of Japan, the latest issue of my friend Leanne’s

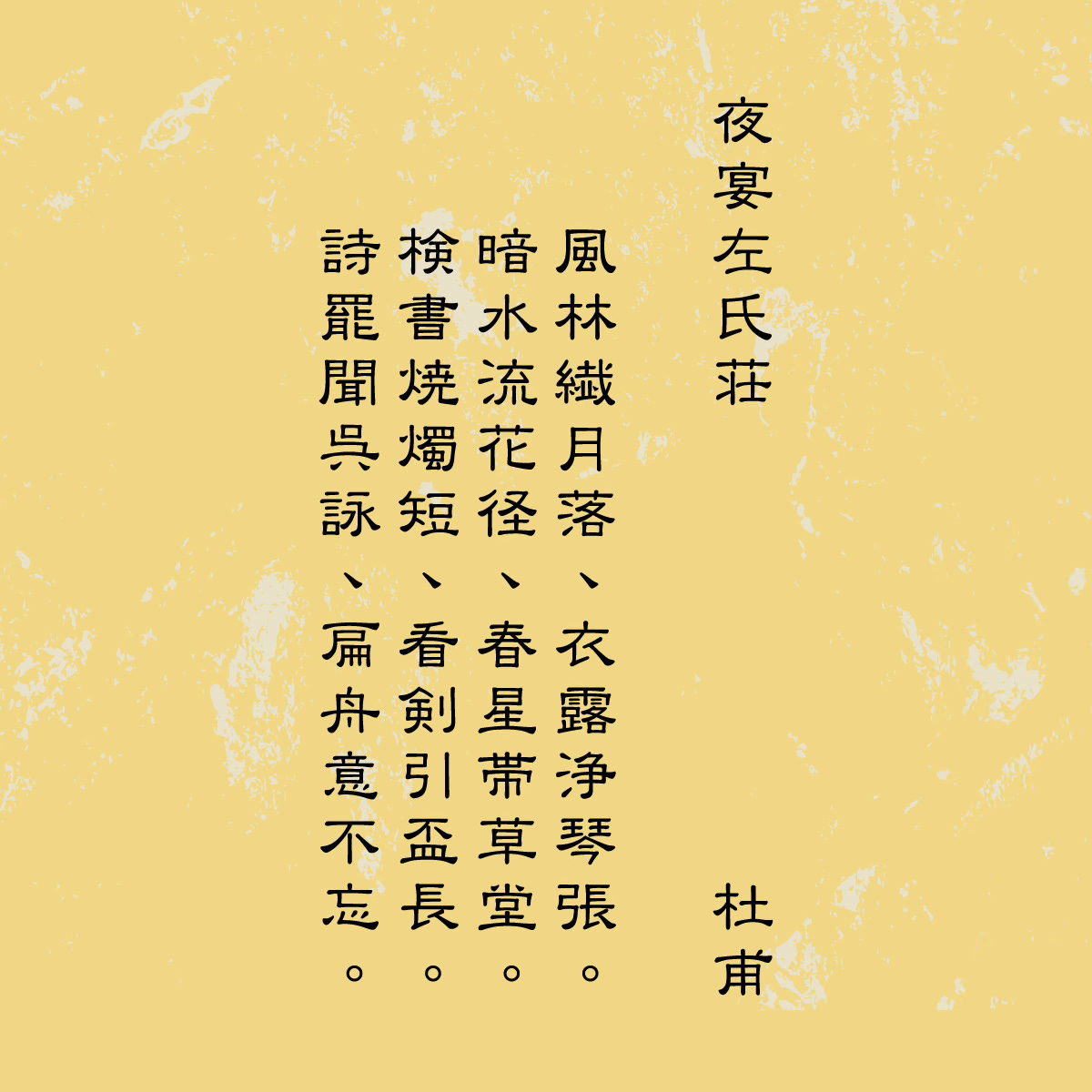

arrived. There are few things I like more for a Sunday afternoon than pondering Tang-era poetry. And so, for Leanne, I offer my (poor) translation of one of Du Fu’s most famous poems, An Evening Banquet at Mr. Zuo’s Country House.As the moon weaves its way downward amid the wind and the trees,

my sleeves grow damp with dew; someone starts playing a zither.

In the dark, I hear the bubbling of the spring and smell the flowers,

and a constellation of spring stars spreads out above the thatched roof.

We read until the candles gutter,

and admire his collection of swords as we drink.

And among the poems, someone sings a song from Wu.

How could I forget Fan Li’s boat ride to retirement?

Read Leanne’s issue for her superior translation as well as the context for that poem.

I almost forgot. Here’s a print of Dejima from the National Library of the Netherlands.

Thank you all for coming on this wandering ride with me. I hope the week ahead is good.

Your translation is gorgeous!!!!!!!!!!!!!