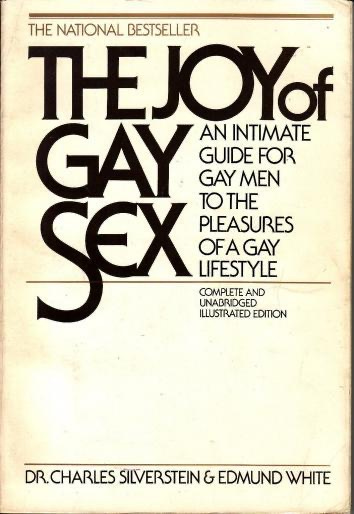

I was eleven years old in 1977, the year that The Joy of Gay Sex, by Dr. Charles Silverstein and Edmund White, was published.

At eleven, I was already aware that men exerted a magnetic pull on me. I had had romantic fantasies about television stars like Bill Bixby (in Courtship of Eddie’s Father, a show which might have also triggered my lifelong love of Japan), John Mantooth (in Emergency), and, in 1977, Erik Estrada (in CHiPs, and please forgive my younger self for not resisting copaganda—Erik’s dark hair and smile were far more important to me than any of the plot lines).

By 1978, perhaps timed to the release of Christopher Reeve’s Superman (more dark hair, more beautiful smiles), my fantasies began to blur from the romantic to the erotic. Puberty arrived early, yes, but with it came a sudden awareness of my seeming solitude in my passions.

Even when, in 1979, I learned—courtesy of magazines I had discovered with titles like Mandate, Blueboy, and Honcho—that many men loved and lusted for other men, I innately knew that my proclivities had to remain a secret. And although I didn’t yet know the terminology, I locked my sexuality into a closet.

Fast forward to 1987.

A dear friend of mine, the Reverend Doctor Carol Pepper (may she rest in power), convinced me at the end of my junior year at Williams College to come out of that closet, if only to myself. To accept my gayness, my proto-queerness.

Her proposed process was simple: stand in front of a mirror and tell yourself, you are gay, and I love you for it.

Her timing for that suggestion was ingenious. I was about to, once again, spend the summer on campus, working in my animal behavior lab, preparing for my senior year thesis on nesting behavior in Mus musculus and Peromyscus leucopus (species of mice, both of them). A few of my friends stayed that summer, too, but I was content to have smashed only one closet, my own.

I forget what prompted me to drive down to Manhattan one weekend that August. But regardless of the reason, I found myself in a bookstore on Christopher Street. I riffled through the pages of a used copy of The Joy of Gay Sex. I confess: it wasn’t the words that caught my eye. And even though the drawings within enticed me, once I returned to Williamstown with the book, I began reading.

Of the many chapters that Edmund White had authored, one in particular prompted me to read, re-read, and keep re-reading. The chapter was on coming out, and it became my dearest reference. In those pages, I learned not only how to exit my closet for other people, but I also learned how other people might react to my revelation.

When the semester began in September, I put my new knowledge into use.

Badly, I admit.

My first attempt, to my dear friend Susan, was so tongue-tied and drawn out that she initially thought I was trying to ask her out. But that first attempt wasn’t particularly revelatory for her: Susan already knew I was gay.

So did Ann Marie, my second coming-out audience.

If people already knew, I wagered, I could accelerate the process. The following Sunday, with all my friends seated at three tables in a corner of the Greylock dining hall, I stood and made an announcement. “Just wanted to let everyone know: I’m gay.”

No gasps of surprise. My friend Bill resurrected a running joke and quoted the first words from Brahms’ Ein deutsches Requiem, “Ja, der Geist spricht!” (Yes, the Holy Spirit speaks!) My friend Courtney clasped my hand as I sat and reminded me that nothing had changed.

In this, I was very fortunate.

But I wasn’t done with Edmund’s wisdom.

When I shared those coming–out successes with Carol, she suggested I level up and face every queer young man’s potential boss battle: our mothers.

From Edmund, I had learned that coming out was best performed in person. And, both nervous and a former theatre kid (duh!), I wrote and memorized a script. During the drive down the Taconic and across the Tappan Zee to my home in West Nyack, I rehearsed. I slowed my talking pace down. I tested the emphasis on different words.

And when the curtains rose and the lights dimmed, my soliloquy went as planned.

Until it didn’t.

My mother broke down in tears at the end. She managed to ask a few of the questions Edmund had me prepared for: What about grandchildren? Won’t you be unhappy?

But there was one question that couldn’t have been on Mr. White’s radar in 1977. What about AIDS?

My answer was perhaps too brief. “I know what I need to know.” I still think that a coming–out moment is not the best time to review one’s knowledge of safer sex techniques, but my mother’s evident sorrow, I admit, made me uncomfortable.

During my preparations, I had, of course, catastrophized. But those imagined worst–case scenarios involved anger and rejection, not grief. Part of me worried that any attempt to console my mother would make the situation worse. My stepfather, who had been at her side throughout my monologue, reassured both of us. In his former life as a social worker, he had worked with and accepted many gay people, he said.

And once my memorized lines had been spoken, there wasn’t much room for extemporaneous sentences.

Before I left, my mother asked me two things: for time to better understand her new awareness of her firstborn, and for silence with regard to my extended family. Knowing my grandfather, not to mention most of my uncles (my mother has four brothers), I agreed.

I left for Japan the following year, extending the time and distance my mother needed. I didn’t come out to siblings, cousins, aunts, and uncles until much later.

Edmund, however, found me in 1988’s Japan, at a bookstore in Tōkyō’s Takadanobaba neighborhood called Byblos. A Boy’s Own Story, the first novel I bought in my new country, once again brought me hope as I struggled within a professional closet for six of my ten years in Japan.

From Edmund, my universe expanded. Books by Felice Picano, Andrew Holleran, Ethan Mordden, Rita Mae Brown, and Armistead Maupin not only comforted me, they inspired me.

Fast forward many years to 2022, and my first writing mentor, Garrard Conley, has read through that year’s version of my memoir’s manuscript. I had mentioned Edmund White in those pages, and Garrard, in that I’ve got a secret way of his that made me value him even more, confided that he had not only met Edmund, but that Edmund was reading through drafts of Garrard’s first work of fiction, All The World Beyond.

I think my fan-girl squealing was audible three states away.

Garrard kindly suggested I follow Edmund’s husband, Michael Carroll, on social media, and my connection to a writing idol grew that much closer.

I had the chance, thanks to Hippocampus Magazine, to document my adulation earlier this year, when Edmund published his latest (final?) memoir, The Loves of My Life. Although my editor asked me to dial back the personal gushing for subsequent reviews, I am glad my ode to Edmund was accepted.

Edmund White died on Tuesday, June 3rd, 2025. Although there have been many accolades in the days since, I share my condolences with all who knew and loved him. Although his words and talent still illuminate my life, I admit to feeling a little dimmer without him in the world.

Every time I drop in to read your posts, I learn a bit more about the beautiful person that you are, and glean insights into the world as you inhabit it. I should do it more often. Cheers, mon ami!