I first started in on meditation during the early months of the pandemic.

At one point, my streak exceeded two hundred daily sessions. Last year, my practice grew sporadic. Maybe, with all the good that was happening, I felt complacent. I had certainly become adept at noticing happiness out of the corner of my eye. I mentally bookmarked each of those moments, a memento felix—remember, thou art fortunate—perhaps knowing that darker moments when my brain attempts to convince me that I have never been happy could return. Perhaps those recollections of joy could, if not light a way forward through the bleakness, at least safeguard my present.

I pray, too. Although not in the way I was once taught to. No more prie-dieus and novenas for me.

And I rely on my amulets and thank them for their protection.

The amulet that keeps me from falling—purchased with deep love and concern by my husband at Kiyomizu Temple in Kyōto the day after I had slipped on a rain-slicked balcony in the mountains of Okayama—is worn with my work badge.

The amulets honoring the deities of my art—Amenouzume (Shintō) and Benzaiten (Buddhism)—together with an amulet from a temple just north of Hilo, in Honomu, where the presiding monk, Reverend Clark Watanabe, prayed with me for writing success, sit near my computer. The prayers in Honomu, said in November of 2023, were particularly effective: five of my essays have been published so far this year, and I was listed as a finalist and awarded an honorable mention for two contests.

There is an amulet in my wallet to shield me from physical harm and, perhaps most importantly, three amulets—two from Sensōji, the temple in Tōkyō where my first date with Hiro began—to protect me as I drive. Gosh knows, as someone who learned to drive in New York and who now contends with Washingtonians and California transplants who consider right-of-way laws, turn signal use, and zipper merges to be conceptually nice but practically unworthy of respect, I need it. (Hiro, who learned to drive here under the tutelage of my wonderful friend Adam, is, without question, a calmer driver than I am.)

Get Back to the Point, Brian

Eighty-five days ago, I returned to my meditation practice and have maintained the daily habit since then.

And yet, the efficacy is waning.

Roughly a month ago, something happened—I won’t share details except to say that it has nothing to do with Hiro or my writing—that has caused me a lot of stress.

The stress over this ongoing something has permeated my psyche: I have nightmares about it and often wake early, obsessing over next-step actions.

Mindfulness, wherein I center on my present, has not been helpful, given how much stress continues to infuse my present.

What, then, should I be doing?

My Super Power

I’m writing.

I’m in the process of developing two new essays. One is tentatively titled Hug Monster, an ode to affection. The other one examines the role of heteronormativity—the biases and assumptions that result from viewing the world with heterosexual filters—in the lives of queer people. Ideally, that latter piece will be ready before National Coming Out Day, October 11, 2024.

I’ve also been revising my newly rechristened manuscript, Crying in a Foreign Language: Coming Out and the Home I Always Wanted. Compared to last November, the structure is tighter and more compelling, but querying is a challenge. And querying also does not mesh with mindfulness because the present is a place of rejections. Literary agents are busy people, and I am more adept at recognizing form-letter replies that boil down to a single sentiment: my work is not a fit for the agent I queried. Which can be, sadly, interpreted in myriad ways.

But sometimes, an agent will reject me with a sentence or two that still encourages. When an agent authentically admires my writing or the concept—describing it as something they’d want to read—but still rejects it, it tells me two things.

Thing one? There is a market for my book, not despite the quirky, researched, hybrid, flash-like (or Polaroid-like) experience of reading it but because of those qualities. Those qualities arose because I chose a structure that maps very closely to my mental state in the late 1980s and early 1990s: fearful, flighty, and anxious.

Thing two? The agent who not only admires the work but also, critically, understands how to market it to publishers is out there. The manuscript is a gamble. It tells a long, complex story as it veers into and out of citations from other authors that let the reader draw their own conclusions as to why I feared HIV/AIDS, why I kept trying to come out of my closets, and why Japan—and one person in particular there—became the home I always wanted.

Again, Brian, the Point?

It’s not the present of mindfulness that can offer me solace.

It’s the past—what I write about—that reminds me, as my mementi felices do, as my amulets do, that happiness was once within my peripheral vision, within my heart.

And it’s the future—where my book exists in the world, where I’m free to write the next book and the book after that, and where I’ve returned to Japan—that reminds me that I will once again glimpse that happiness over my shoulder.

The stresses of the present wake me from sleep and demand my obsessing. But a few days ago, I discovered a cheat that takes me away from the present. I fell back asleep and then dreamed of my future—one where Hiro and I are touring homes in Japan, choosing our forever home. I luxuriate in a future where the problems of the present no longer matter.

One More Future

Two superior courts in Japan are expected to reach verdicts in marriage equality cases later this year. Public opinion has already shifted—most Japanese people support marriage equality—and many, myself included, believe that legal and legislative shifts are coming to make marriage equality a reality.

I therefore believe that by the time I retire (in 2031? 2033?) I will be allowed to enter Japan as the spouse of a citizen. If I am afforded the opportunity to claim Japanese citizenship at some future point, I will. And if memory serves, I will need a Japanese name for my new passport.

I have dreamed of Japanese citizenship in the past and have often assumed that I could repurpose the name my coworkers at my first job in Japan offered me. They read the characters they chose, 和戸村, as Watoson, a good approximation of Watson. But 和戸村 can also be read as Wadomura, which would be an excellent name, too.

But I brought up the name issue with Hiro the other day. Setting aside the more straightforward question of my given name—Brian derives from an Erse word meaning strong, and many Japanese names offer identical connotations: 剛, 強, 健, 赳, 幹, 毅, 勁, etc., all of which can be read as Tsuyoshi; I’d probably choose an uncharacteristically butcher option, like 豪太 (Gōta, meaning strong and stout).

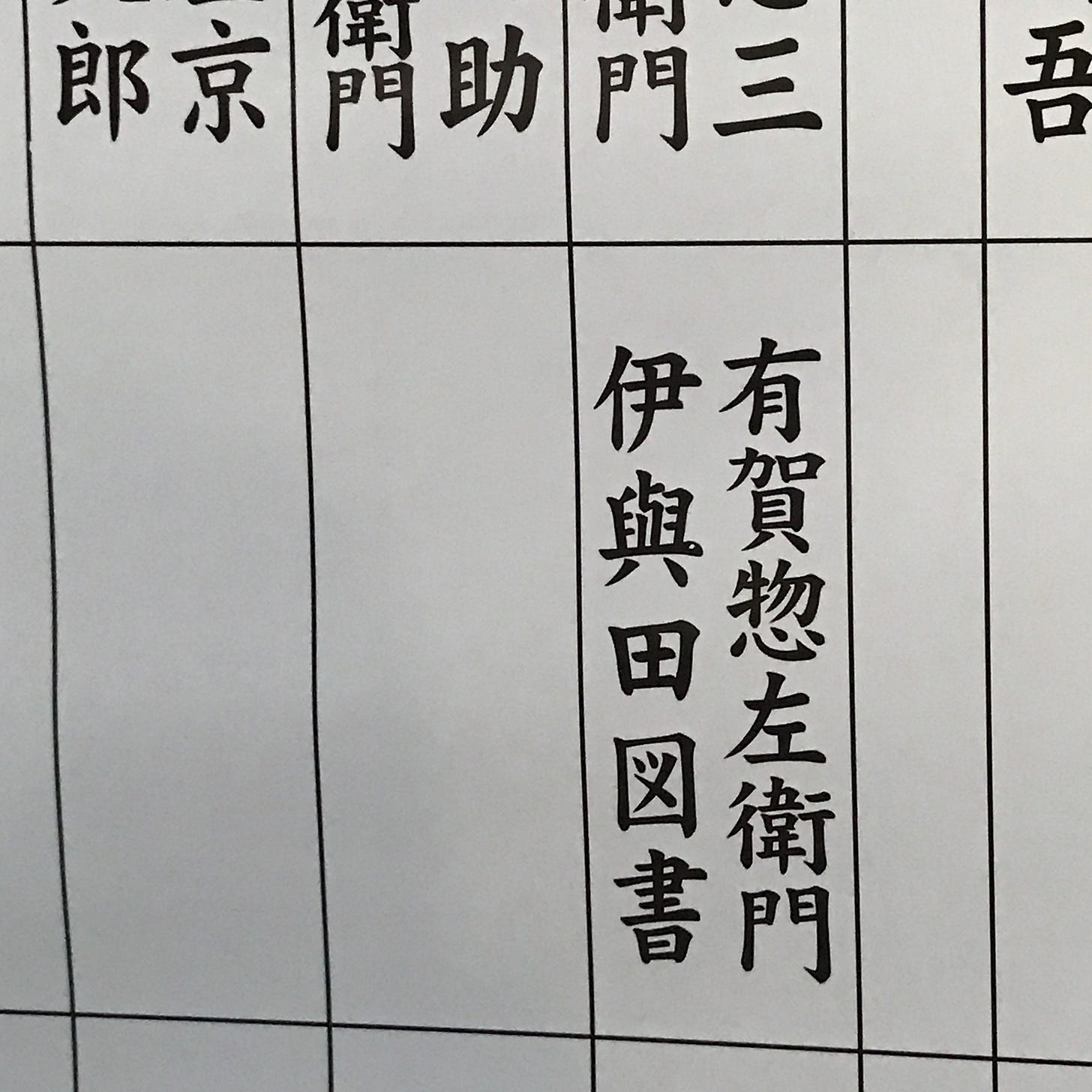

During that conversation, however, I asked Hiro how he’d feel if I took his family name, 有賀 (Ariga). It’s not a particularly common name—it ranks 860th among Japanese family names, with most Ariga families in Nagano and Fukushima prefectures (where Hiro’s father is from). It’s also a samurai family name—I found it on the roster of teachers at an eighteenth- and nineteenth-century school for samurai children in Fukushima during a 2016 visit with Hiro.

Hiro’s response was, true-to-form, quiet and sweet.

If you want to take my name, it’d make me happy.

I love making him happy.

In Conclusion

I’m not a fan of the right now.

But damn, do I have a lot to look forward to.

What you said about writing! You are so blessed with love!!!