Pride and Joy

Japan might have been the worst destination after coming out. Thank goodness I didn't know that before I went.

The year is 1988. Let’s say February.

I’m six months into my lifelong coming-out process. My friends are all cool with it. My mother? Not so much. We have barely spoken since the day in late September when I broke the news of who I am to her.

My last semester at college has begun. I’m conducting final experiments for my thesis project (I wanted to graduate with honors in Biology after abandoning pre-med dreams). Because I’m a science major, a lot of my science classmates are heading to graduate school. I am not. Two years of animal behavior research (performing countless pap smears on lab mice—if I hadn’t been queer before that, I would have been after!) prompted me to lie to my thesis advisor: I want to take a year off before grad school.

I’ve been studying Japanese for two and a half years at this point and I’m very good at it, despite the fact that I never visit the language lab to study. Without much else of a future in mind, and with an increasing sense of panic as the rate of HIV-AIDS infections skyrocket, I decide to apply for a job in Japan.

It’s a cowardly decision. Coming-out had unleashed my natural vibrance into a new direction of authenticity and advocacy. But HIV-AIDS terrifies me. No treatments have been deployed yet, and the growing gloom for each diagnosis convinces me that remaining in the US is a death sentence.

Coming out, however, created new insecurities to counteract that authenticity. As certain as I was that I would contract HIV-AIDS and die from it in the US, another part of me mocked that confidence. I was the only fat gay man I knew (my college was really small and quite isolated). Nobody at that college was sexually interested in me after I came out. How would I get HIV-AIDS if nobody wanted me.

That, as they say, is fucked up. I was twenty-two, still a baby queer, and just beginning to recover from a lot of childhood and teenage bizarreness. And of course, hindsight lets fifty-seven-years-old me see all of that terror and insecurity, but me in 1988? All I knew was escape and avoidance.

I flew out of JFK late in Japan with a cohort of other tristate residents who were all headed to the same job: assistant English teachers within the Japanese school system. Days after I arrived, however, officials running this teaching program told me to re-enter the closet. Think of the publicity, they said. The bad press. An angry PTA.

After three months in homestays (that’s a nightmare for another story), I moved into my very own apartment at the end of October. The next month, I had to attend a teaching conference, and at last met another gay person. Cameron has shockingly blue eyes, scruffy blond hair, a Virginia Slims habit, and a wit as icy as mine. We become friends in seconds after I joke about teaching PTA members to cook in English. Whip? Beat? Is this cuisine or sadomasochism?

Through Cameron’s kind guidance and a lot of late night phone calls (the phone company charged for long distance calls back then and Cameron lived two prefectures away from me on the other side of Tōkyō), I learned how to be queer on my own time. Weekend nights were soon spent in the gay-bar-embrace of other men, and by February of 1989 I had realized that there were men who actually preferred chubby men (in English, I realized, they call themselves chubby chasers, but in Japanese, the term is デブ専, debusen, chubby specialists) and there were bars specifically for me.

Had I not spoken (and read) Japanese, all of that would have been challenging to discover. There’s nothing quite like the moment when your Caucasian self crosses the threshold into a Japanese gay bar. Dozens of eyes grow wide in concern? Do we have to speak English?!

I bowed, winked, and uttered a simple ごめんください! (gomen kudasai! the customary customer’s hello), watching as the panic amid the assembled patrons melted into relief.

For six of my ten years in Japan, I maintained a professional closet, complete with code-switching galore. My spoken Japanese remained soft and gentle, just as my teachers at college had taught me, and although I occasionally tried to butch it up, shifting from polite speech to direct speech, my colleagues took my aside to remind me that macho didn’t suit me. My closet was clearly more transparent than I thought.

But those six years encompassed a metric shit-ton of joy. I learned to live on my own in a foreign country. My Japanese got so good that I passed the highest level of the proficiency exam and started translating. I met one handsome, sexy man after the next and learned to embody a physical confidence for the first time ever.

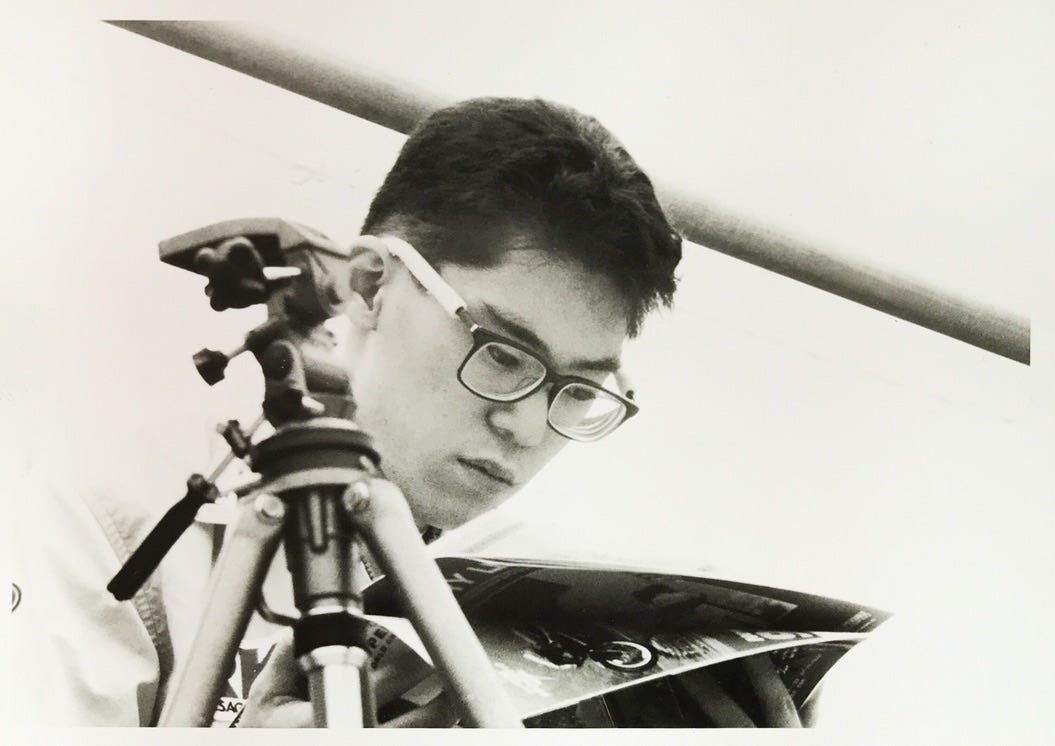

And then, during the fifth year, late in 1993, I met the source of all subsequent pride and joy.

When I graduated college, my maternal grandfather was convinced I was heading to Japan to find, as he phrased it in his constantly borderline racist way, a quiet little wife. I scoffed when he said it and although Hiro is neither quiet, nor little, nor anything resembling a wife, we found each other. I wish, back in 2001 when my sister got married, I had introduced Hiro to my grandfather as my unrestrained, imposing husband, but a) he wouldn’t have remembered his remark from 1988 like I did and b) my mother didn’t need any of the crap from her father that such an introduction would have unleashed.

But it didn’t matter. Japan had taught me many things. My closet could have a revolving door when needed, but there was still joy to be had within it.

So much to love in this post! "metric shit-ton of joy" "Closet or no closet, I am queer in satellite photos"--I laughed out loud at that one :)