I had an apartment in Tōkyō from 1994 to 1998.

Hiro and I had begun dating six months before I moved to the big city, but he didn’t move in with me. His home with his parents was on the other side of the metropolis—I lived in Shinjuku Ward and he lived in Edogawa Ward—and an attempt at cohabitation would have prompted too many questions from his parents. His father, in particular, was keen to maintain his ignorance regarding our coupledom.

Even so, we were together more than we were apart. Weekends were spent at my place, and he headed in my direction after work multiple times during the workweek. In those years, he earned his keep at a print shop and when he wasn’t color-correcting for his clients, he and his boss authored one of the first books on Adobe Photoshop in Japanese. QED, he worked long hours, but he had a key and I loved hearing that key turn in my lock, the way he padded across the kitchen to the bedroom, and how he gently crawled into bed beside me.

To maintain my visa for life in Japan, I found a new job in 1995. I worked for the eminently intelligent

at his software localization, Pacifitech, in Yokohama and commuted from Shinjuku (via a bus to Mejiro Station, the Yamanote Line to Shibuya Station, the Tōkyū Tōyoko Line to Kikuna Station, and the Yokohama Line to Shin-Yokohama Station—Hiro admired how the many flights of stairs along that commute sculpted my calves).One morning in December of 1996, however, during the walk from Shin-Yokohama Station to the office, I became suddenly and violently ill, dousing some already bedraggled bushes by a construction site with bilious vomit. I fished my yellow candy-bar phone from my pocket and, after a call to work asking for the day off, called Hiro and said I was retracing my steps and heading home.

That night, Hiro begged off working late and came to my apartment earlier than usual. I was still sick—in Japanese, we say your complexion is blue, not white—and had not been able to hold anything down. Hiro called a cab, and ferried me to the closest hospital, Seibō (Holy Mother Mary). Yes, a Catholic hospital.

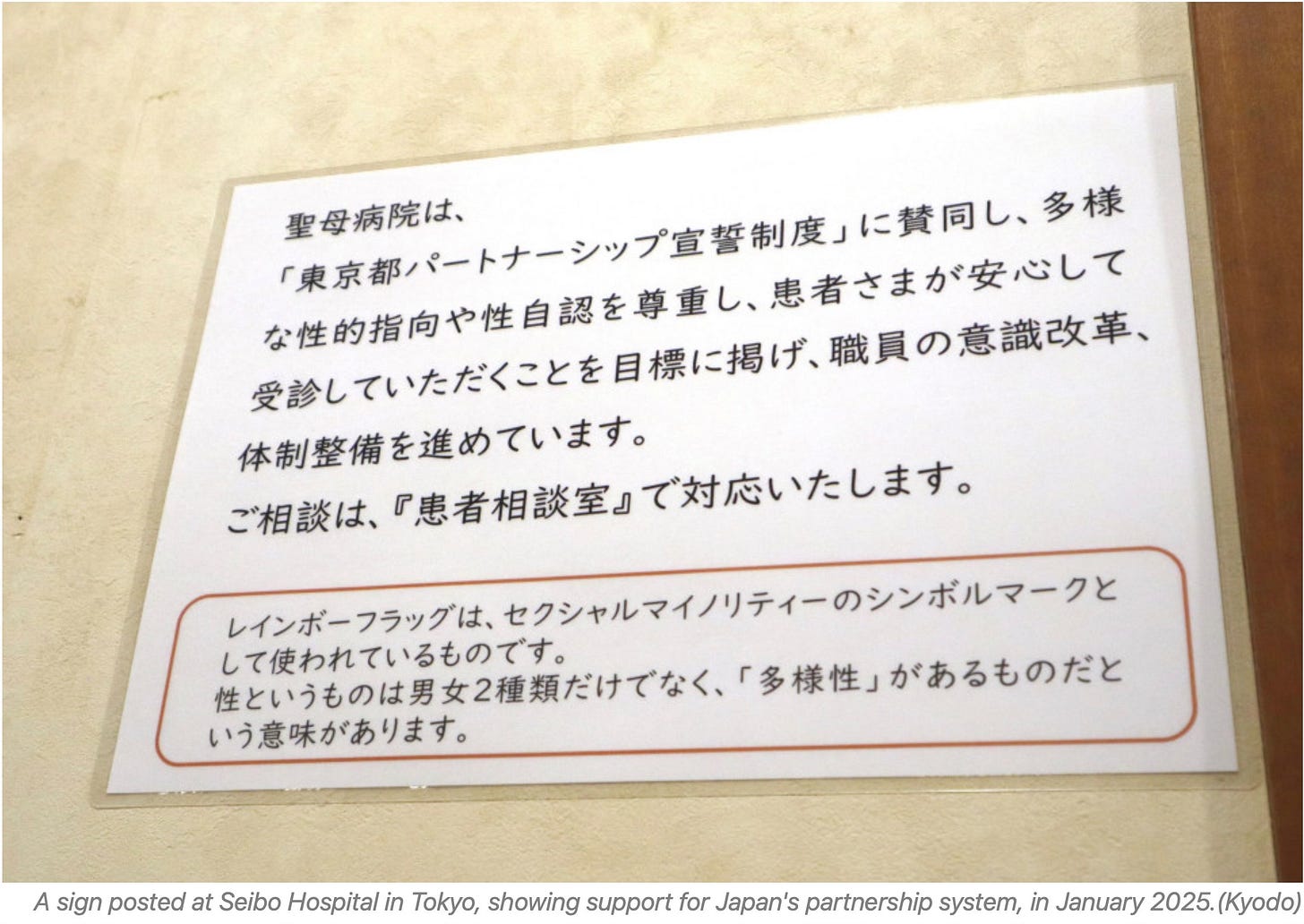

I go into greater detail on my adventures there within my memoir’s manuscript, but the reason I’ve been thinking about that hospital is here. Even Seibō is becoming a more inclusive space for queer couples under the terms of the separate-and-as-yet-unequal partnership system that the Tōkyō Metropolitan Government adopted. Here’s the money shot from that article.

Setting aside the slight, yet still welcome, reinterpretation of the Rainbow Flag, I cannot stress how amazed I am to see this. At the same time, I should also note that neither I nor Hiro experienced any discrimination at the hospital when I was a patient there, aside from my gest that the lack of private rooms was homophobic. Hiro faced no barriers when visiting me, and although the staff might have realized that we were more than just friends—which was how we introduced one another to them—they never objected to our relationship and, when (on Christmas Eve) it was clear that my doctor there couldn’t divine the cause of my injury and wanted to transfer me to the much larger Ward Hospital, she let Hiro ride in the ambulance with me.

Japan’s progress on recognition and honoring of same-sex couples has astounded me, given how slowly social progress usually occurs there.

Speaking of progress…

This tweet from Marriage For All Japan arrived in my Twitter notifications Thursday evening. The fourth high court in Japan, this time in Nagoya, has ruled that any bars to marriage equality violate Japan’s constitution. Allow me to translate:

All we now need is legislation!!!

The Nagoya High Court has, in accord with lower court rulings, ruled [the marriage equality ban to be] unconstitutional!

The ban violates both Paragraph 1 of Article 14 [“All of the people are equal under the law and there shall be no discrimination in political, economic or social relations because of race, creed, sex, social status or family origin.”] and Paragraph 2 of Article 24 [“With regard to choice of spouse, property rights, inheritance, choice of domicile, divorce and other matters pertaining to marriage and the family, laws shall be enacted from the standpoint of individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes.”].

This is the fourth high court ruling of unconstitutionality, and it is very rare for this many courts to agree on such matters. That is a reflection of how bad things are in Japan [for same-sex couples].

And yet, neither the government nor the Diet has acted.

We ask that the government and the Diet move, without delay, to marriage equality legislation.

House of Councillors elections are in July. We will continue to make our voices heard and hope all who can vote in Japan will cast their ballots.

#NagoyaHighCourt0307

#FreedomToMarryForAll

As noted, Nagoya is the fourth high court, following on Sapporo, Fukuoka, and Tōkyō, to rule in favor of marriage equality. The verdict for a similar case before the Ōsaka High Court will be read out later this month. And the Japan Supreme Court shall rule next year.

Given the recent disappointment regarding visas for same-sex couples in Japan, both Hiro and I are looking forward to marriage equality legislation. I’m looking forward to a renewal of vows in Japan, and to the day I can apply for Japanese citizenship (and officially take my husband’s name as mine—I think Brian Ariga has a beautiful ring to it).

I want to end with some data from my querying adventures for Crying in a Foreign Language, my first memoir.

Since the re-completion of my proposal (thank you, again,

) and the last spurt of revisions to the manuscript last April, I have queried 141 literary agents.Of those, 52 agents never responded, 49 sent form rejections, 6 sent personalized rejections, and one asked for the full manuscript (and she is still reviewing it—gratefully so!). I am also waiting to hear back from 33 agents, so the numbers will continue to change.

(Hiro asked last night why I was still querying and waiting on other agents when the one agent asked for the manuscript. That agent might reject the manuscript, but even if she likes it and comes forward with an offer of representation, writers are still empowered to remind other agents (who haven’t yet responded) that an offer has arrived. In an ideal scenario, a writer can interview several competing agents with offers and decide which of them is best suited to partner for the success of their book.)

I wouldn’t be the data geek that I am without sharing a visualization of querying life:

I also calculated the average response time: 27 days. The shortest response was less than three hours. The longest? 259 days.

I’ve also recently completed the first draft of a new essay on my clashes between trust and insecurity. I wrote it out longhand in my plain Muji journal (at right in the photo, above), and am using my special edition of Seven Drafts (the one with the mistakenly large typeface—lol), written by writer friend extraordinaire, Allison K. Williams, to revise it. It’s a longshot, but I’m aiming for the Modern Love column in the New York Times. Cross your fingers.