I just finished the kind of memoir where my silence is not an option. Part of this outpouring is despair: I will never, I think to myself, write as sweetly about friendship and death as Hua Hsu does in Stay True.

Yes, it’s odd for me to delve into another memoir in a newsletter that, for the most part, focuses on my lived experiences and my writing, but I hope I can convince you, gentle reader, of why I had to go here today.

Hua Hsu, in Stay True, paints a glorious picture of love. He teaches me how to survive that unique type of keening love that is grief. I was reminded of something another author, Jamie Anderson, once wrote:

[Grief is] all the love you want to give, but cannot. All that unspent love gathers up in the corners of your eyes, the lump in your throat, and in that hollow part of your chest. Grief is just love with no place to go.

That love is one I realized dwells within me as I read Hua Hsu talk about how his friendship with Ken developed, strengthened and flourished, and then expanded and transformed after Ken’s sudden, nonsensical death.

In Stay True, Hua Hsu describes how his surviving love helped him see how his ongoing writing pushed backward into the past where his friend still lived, where the friendship still sparkled. Hua Hsu also reminds us how the writing his friend had once done continued to push forward into Hua Hsu’s present and future.

I know those feelings, having both my father’s writing from before his early death and my writings, and I’ve described that interaction (clumsily) as a portal.

There is magic in writing. Writing is precise, yet vague. Direct, yet malleable. And the emotions that overwhelm me when reading writing like Hua Hsu’s, like my father’s, like mine, even, defy apprehension. I sense those emotions and describe them, desperate to capture that fleeting glimpse of their nanosecond of clarity from a corner of my mind’s eye.

And yet, at the same time, Hua Hsu reminded me that writing also intentionally separates me from that clarity’s present even as the attempt to pen the clarity bathes me in a past gone from me.

Writing offered a way to live outside the present, skipping over its textures and slowness, converting the present into language, thinking about language rather than being present at all.

When I write about my father, in essays and in my memoir, when I write about former lives—most especially the me I once was—and so many former loves, I more deeply understand that memory is, as Hua Hsu frames it, a burning, dying chaos.

[Writing is a] way to loot and hoard in a city on fire, to impose structure on chaos, to download the contents of a storage drive before it succumbed to corruption.

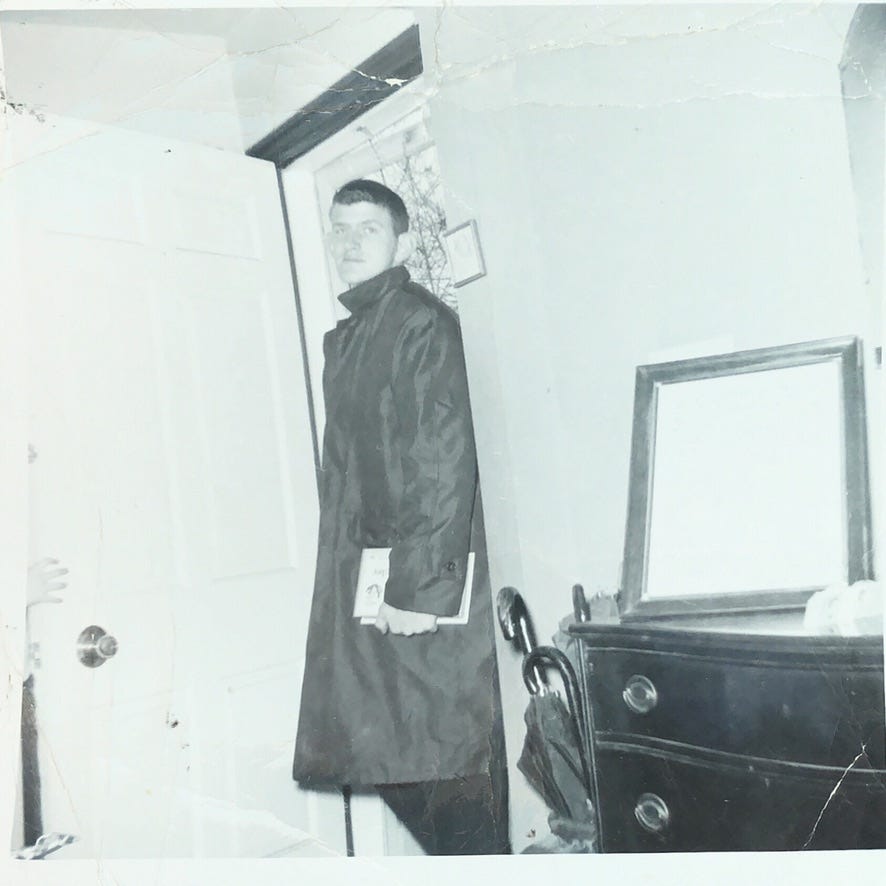

My father was not a writer. Born in 1942 and possessed of an intelligence that had him skipping grades and starting high school at age twelve, he found it easier to get by instead of excel and after a month on a scholarship at Fordham, he signed up for the army, with his mother’s permission, at age sixteen in 1957, two years after his father died. He served as a parts clerk on a missile base in Georgia before getting a swap assignment to a base in New Jersey (closer to home—he was born and raised in Pearl River, New York.

He studied at Fort Belvoir, hoping to make it into West Point, but two factors prevented his ultimate success there: his high school transcript was terrible and he was not in the habit of squealing on other soldiers. He then when on to Fort Bragg, where he served as a company clerk until his discharge in 1963, mere months before the number of soldiers shipping off to Vietnam began to dramatically increase.

A month before discharge I met my future wife, Betty, at a young adults club meeting at my old hanging out place, the church hall. We hit it off so well that after the second date, Betty asked, “When are you going to ask me to marry you?” and I said, “Right now.” We were unofficially engaged in March of 1963 but we were forced to hold off on announcing until my brother Jude became married that forthcoming June. Hence Independence Day I announced my plans to be independent for and dependent upon Betty, and she for me.

In July of 1963, my father was twenty-one. My mother was nineteen—she’d turn twenty in September of that year. They married in January of 1964.

My father was a workaholic, and when he wasn’t at the bank he was with his friends at the volunteer firehouse in Pearl River. He certainly wasn’t writing as my mother fumed at being left alone, first at their small home in West Nyack, near her parents’ place, and then at their split level in a small community called Westbrookville, in rural Orange County, New York. (The address was 69 Manor Lane—hello, foreshadowing!)

To return to Hua Hsu:

[W]hat is history? Do you see yourself in it? Where did you find your models for being in the world? How did you learn about love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice?

My father had his first heart attack in January of 1971, right around his seventh wedding anniversary and my fifth birthday. Aside from brief missives sent to both my younger brother and I during the months he was in recovery from various bypass surgeries—the heart attacks kept coming—he didn’t write. The paragraph I quoted above is from a stenography pad a family friend forced into this hands early in 1980. Helen, the friend, knew as well as everyone else that he was dying. Forced to retire in 1976 with no pension or benefits, we lived in a dirt-cheap Victorian fixer-upper in Nyack, New York, and by 1980 the sun room, a small room off the living room with mullioned windows on three sides, looking out on the intersection of Fourth Avenue and Jefferson, had become the hospital room.

A rented hospital and an oxygen tank were there, and my father spent every hour there, slowly and fitfully writing. The pain he endured may have kept him from writing extensively, and I also suspect his humility kept him from going into too many details. In total I have less than ten thousand words in his hand, and although he speaks to me and each of my siblings in places, I see the whole not as a time capsule, static and immutable, but as part of a connecting portal.

The portal—my father’s writing pushing to connect, connect, and connect with my present and future, and my writing pushing backward to connect, yes, but also reassure and console both him and me—lets me place myself within a history. It reminds me where the things I treasure most—love, pride, compassion—began and then transformed.

There are writers, I must assume, for whom this concept of a written bridge over grief rings insincere. Not all know sorrow. Not all perceive it or respond to it in similar ways. But I found resonance in Stay True. Maybe you will, too.

One last thing. My writing mentor, Garrard Conley, author of Boy Erased, has his first work of fiction, a queer romance set in, hold onto your capotains, Puritan New England. I’ve pre-ordered my copy of All The World Beside and I can’t wait to read it.

By the way, capotains are those flat-topped hats that Puritan men were always depicted in. #TheMoreYouKnow

I resonate with this - writing as a bridge over grief. As you say, not everyone, not every writer, knows grief. But those who know it must write or speak it. What’s that famous line in Macbeth? “Give sorrow words; the grief that does not speak knits up the o’er-fraught heart and bids it break.” In the language of my family’s faith community-your father’s, too-we would talk about the cloud of witnesses and the thinness of the veil. Perhaps can be a way of telescoping time and space - finding that portal, as you say.