I got lost in the middle of this issue, so I put my writing aside for the weekend to see if that helped…

I work a hybrid schedule and must spend at least eight hours each week onsite at my job. (The rest of the time, I very, very gratefully work from home.)

While at the onsite office last Thursday, I was lucky to run into a dear friend, someone who always shares a smile and loving encouragement. Truth be told, many people at the office fit that bill, but this particular dear friend offered a hug and then a belated happy birthday. (Remember, kids, it’s the wishing of the “happy birthday” that is belated, and not the birthday itself, hence a “belated happy birthday” and never a “happy belated birthday.” </pedant>)

And because my dear friend remembered that my birthday had marked my sixtieth full revolution around our star, he went on to say, “You are a queer miracle.” Seconds later, after we had parted ways, I had one of those esprit d’escalier moments and realized a new portmanteau: I am a queeracle!

And I am. Not only is there the miracle of my own health, bafflingly good in the face of a terrible family history—my father died at age 38, when I was 14, and my father’s father, Frederick Gilbert Watson, died at age 48, when my father was 13—there is the miracle of my survival within the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Some of the first United States AIDS cases were detected during the same year I became a sexually aware (and soon to be sexually active) teenager.

I have few queer elders to rely on because my government willfully ignored their deaths during that pandemic’s first decade. Because my government refused to act on prevention, on cures, on any mitigation. And although the greatest number of North American queer AIDS deaths during that decade were among the Baby Boom generation, Gen X was not spared. The antiviral treatments arrived in the 1990s, however, and more of my coevals were at last offered an escape from the AIDS death sentence. The death sentence I had fled to Japan to avoid.

I’m also, at sixty, in the oldest group of Gen X kids. Raised on LPs, and although I’d only ever seen a few eight-track tapes, I seamlessly switched from records to cassette tapes, to compact discs, to iPods, to Apple Music. (I’m not a Spotify gal.) I was around when the first personal computers arrived on scene, and although my first computer, purchased in 1984 before heading to college, was an Apple IIc (because, at seven odd pounds, it was “portable,” but the little CRT monitor it came with more than doubled that weight), I switched to a Macintosh in 1986 and never looked back. (And the email address for Apple’s CEO, Tim Cook, is tcook@apple.com, in case you’re of a mind to tell him that Apple customers don’t want him to be a Trump administration stooge.)

My age has me tempted to update the lyrics to Sondheim’s I’m Still Here (as sung, of course, by Elaine Stritch).

Good times and bad times, I’ve seen them all and, my dear, I’m still here.

Sweet champagne sometimes, sometimes just Sapporo beer, but I’m here.

That’s about as far as I get. It’s hard to beat Sondheim when it comes to lyrics.

It’s fascinating to think that high-end technology for my parents, around the time I was born, was color televisions and high-fidelity stereo sound. Technicolor movies and the mainframe computers that filled an entire room at the bank where my father worked. I watched television as a child, and listened to my parents’ albums—my mother’s Christmas music and my father’s Bob Newhart and Broadway musical albums—but playtime was riding my bike and, on the sly, playing with Barbara, the girl who lived next door, because she had Barbie dolls. I learned to read at a young age, too. Doctor Seuss, at first, and on to Nancy Drew and The Bobbsey Twins. Another favorite childhood pastime was pretending to be a beautician—taking my cues from my mother, who lovingly did her mother-in-law’s hair for her. Except my customers were my stuffed animals, and I repurposed my Fisher-Price Little People toys as cosmetics.

Although long-time readers know of my tendency to wax nostalgic, I’m going to change gears.

At some point in 2020, before I started work on my memoir’s first draft, I was working on another creative project. Several ukiyo-e prints and paintings are available online as museum and library scans. Many are of high enough resolution for me to work them into new Photoshop files with a drop shadow background. As an example, here’s a painting by Hiroshige of the folkhero, Momotaro, with a background sized for easier framing.

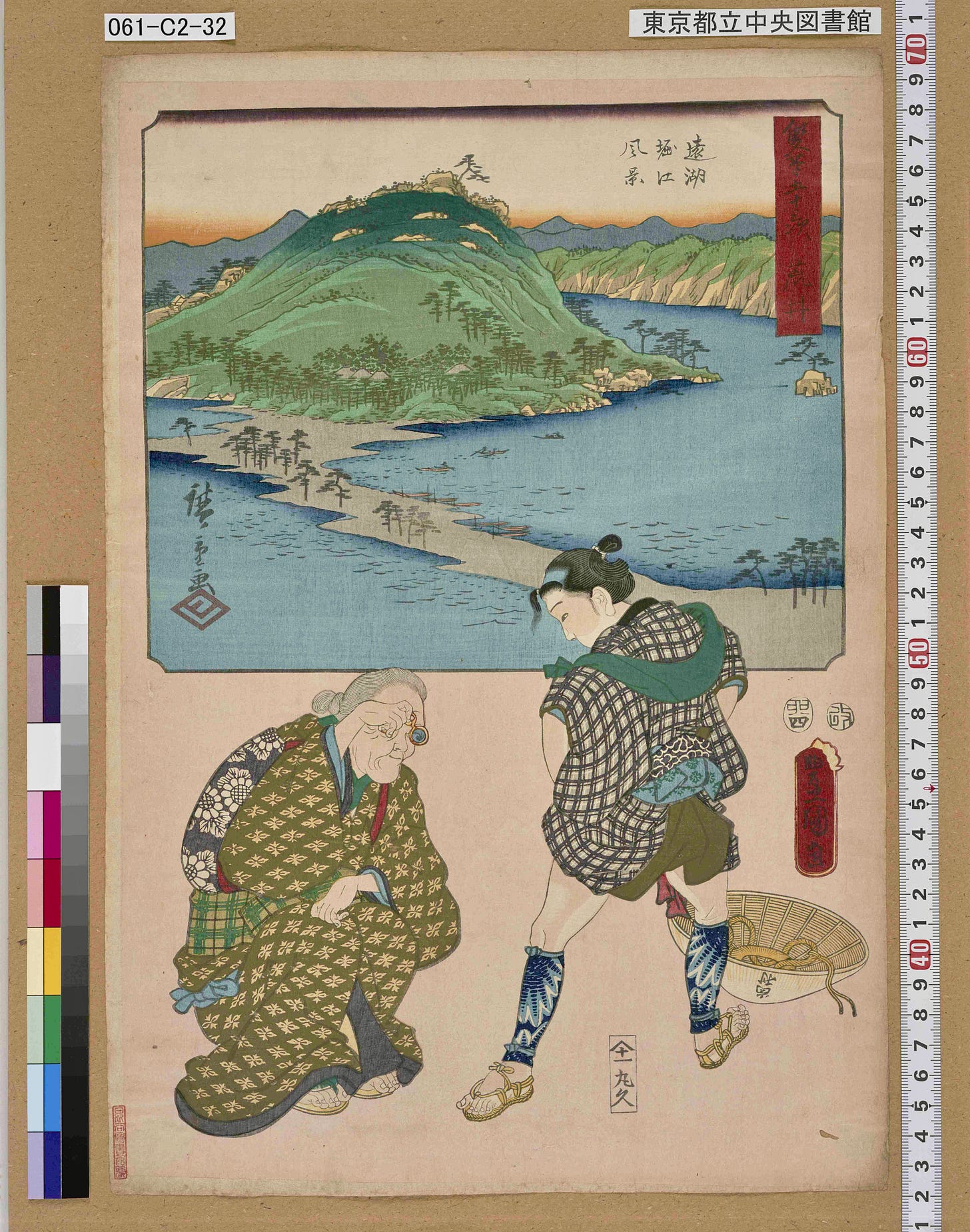

One of the Hiroshige prints I found had been scanned by the Tōkyō Municipal Central Library.

This print is from a series depicting the 53 stops along the Tōkaidō, the coastal road from Edo (now Tōkyō) to Kyōto. The stop in question is Arai, now located in the city of Kosai, in western Shizuoka Prefecture. Arai was a type of border town, the penultimate stop within the old domain of Tōtōmi before reaching the domain of Mikawa (most of which is in present-day Aichi Prefecture, at Japan’s center).

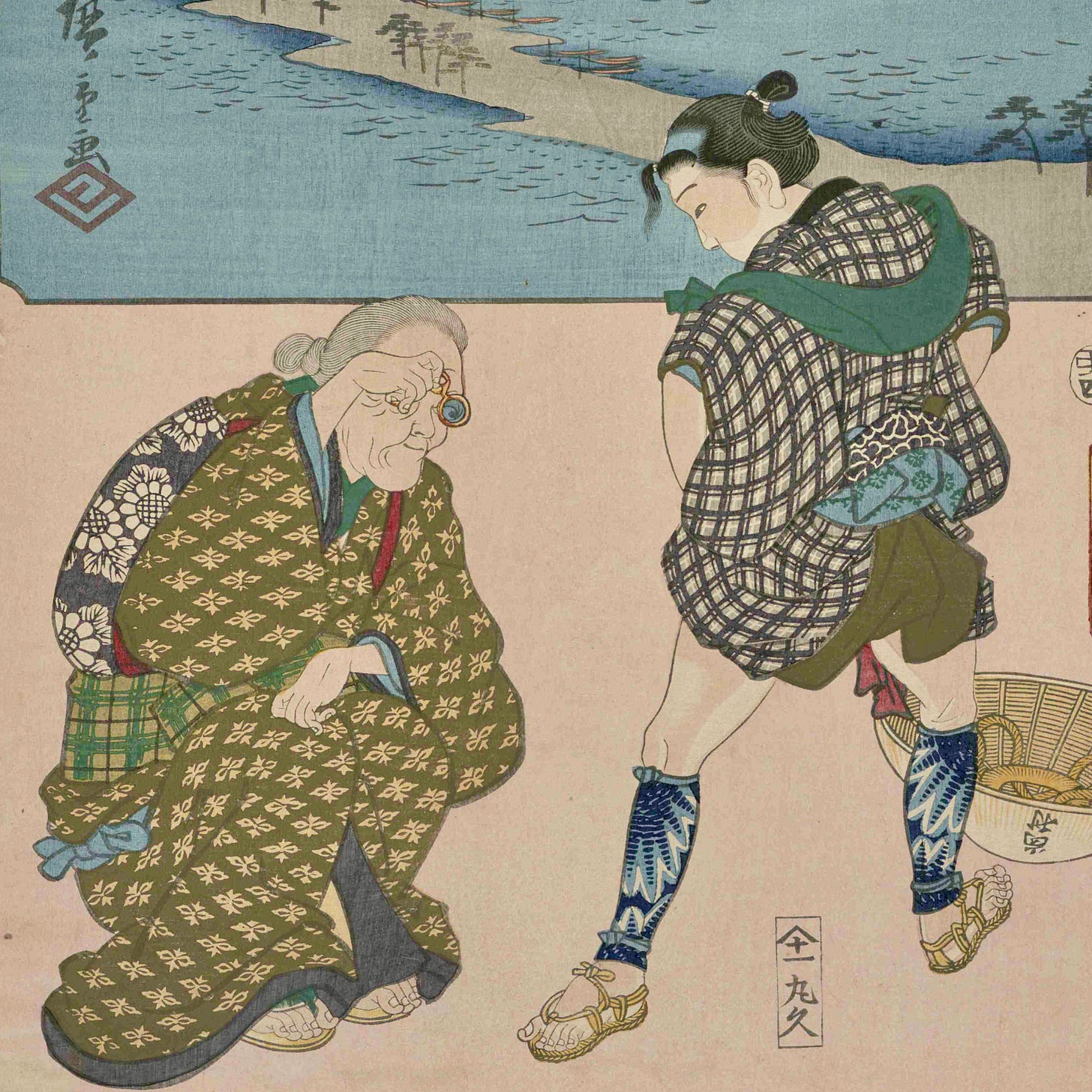

Although the upper half of the print is a lakeshore landscape (Kosai is written as 湖西, and means west of the lake) with some of Hiroshige’s signature techniques—the abstracted trees, the gradients near the shore and at the horizon‚ it was the bottom half (pun intended) of the print that took me by surprise. What the heck is going on? (And, as Allison K Williams once rightly noted, those tie-dye gaiters are amowzing—amazing with extra wow.)

I did some research, and although I covered this in a pre-Substack blog post, I want to revisit it for several reasons.

The young man in the print is likely between the ages of thirteen and nineteen. At age twenty, he would have had that forelock of hair (on his forehead) shaved off and would fully commit to the hairstyle of the adult men, the 丁髷 (chonmage), that we still see among professional sumo wrestlers.

Young men rarely developed facial hair at that age.

Women were not allowed to travel on their own. They could escape bad marriages or bad employers by fleeing to the nearest Buddhist convent, but some women hoped to get even further away from abuse.

Women were therefore known to disguise themselves as young men and flee.

During that period in Japan’s history, the five great highways, three of which connected Kyōto and Edo, and two of which aimed north from Edo, were patrolled and safe to travel without worrying about thieves and cutthroats. Traveling away from those thoroughfares, however, required bodyguards.

The Shōgun, Japan’s de facto ruler at the time, had every interest in maintaining the social order. Social stability meant the potential for an uprising was low, and rulers liked to remain in power without the threat of uprisings. The Tokugawa Shogunate was so stable that it lasted for nearly three hundred years.

That social order did not want women to have the ability to go wherever they wanted to. High-ranking women certainly traveled, but always with retinues, and nearly always within a palanquin that kept them from view of passers-by.

How then, would a shogun prevent women in bad situations from disguising themselves as men so they could travel more freely?

Enter the 改め婆 (aratame baba), the old woman who makes sure. It was her job to review the genitalia of young travelers, to make sure that solo travelers had external ones below their torsos. Speaking of torsos, I suppose that the old women could also review chests, but not all of the women who had cause to flee were old enough to develop breasts.

The social mores of Japan at that time attributed sexual agency to adolescents, something (most modern, normal, non-billionaire, non-friends-of-Epstein North Americans would not). Although both girls and boys were allowed to make sexual choices from age thirteen onwards, such expressions of sexuality were controlled.

Girls of low social standing were often sold to become apprentices within entertainment districts in Edo, Kyōto, and Ōsaka (then called Naniwa). They were taught how to avoid pregnancy and how to refuse clients (although most were not given the liberty to refuse).

Boys of low standing sometimes did the same, or were apprenticed to the great kabuki theatres. Their first roles were usually off-stage, vying for the patronage of theatre fans, both adult women and men. But for boys of higher standing, there were other venues for sex, ones that offered much more liberty.

I’ll talk about the contracts drawn up between monks and acolytes, and between samurai and squires, in the next issue. But for now, I want to note an odd coincidence. Setting aside the oddness of needing a magnifying monocle to view genitalia, let’s zoom in on our old woman in her government-appointed role.

And let’s now look at the flag of the city of Kosai, where, when it was known as Arai, this old woman worked.

It’s giving eye in a monocle vibes. Or is that just me?

I love queeracle - and the mushroom beret! Thanks for the lesson on Japanese culture.

You are indeed a Queeracle, my dear. I think you should look into a monocle, you could carry that off with pizazz. And the way you take us through a painting or a book is beyond beyond! Promise you'll review mine when published. lol