I observed a critical anniversary this past week. At the end of July in 1988, I boarded a plane, a Northwest flight from LaGuardia to Narita. I arrived in Japan on July 31 and woke, for the first time, in my new country on August 1.

One of my professors at Williams, Peter Frost, who taught my class on Modern Japanese History, took me aside late in my senior year, after I had learned I had been accepted into the Japan Exchange and Teaching Programme and would be traveling there shortly after graduating.

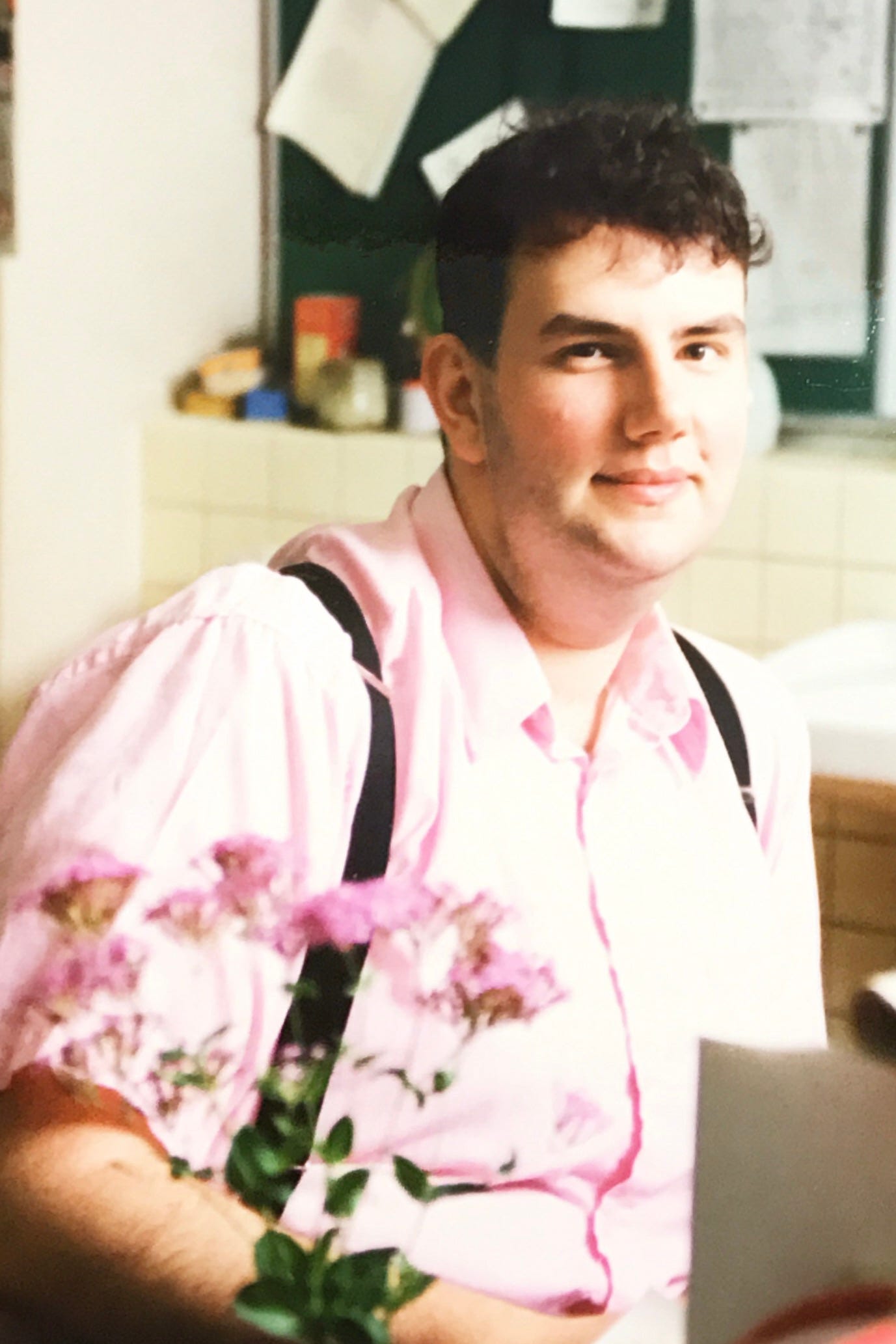

He said, “With your height and weight, Brian, you will stand out in Japan. I think you should shave off your beard so there’ll be one less thing for people to comment on.”

Dr. Frost, as is the wont for most male professors of an alabaster hue, believed his advice to be sage, and I, still an impressionable and eager-to-please young thing, followed his recommendation. July 31 is, therefore, not only the start of my ten years in Japan, it is the start of the only three years of my adult life spent without the allure of facial hair.

I have been writing and rewriting this issue of Out of Japan for two weeks.

I’m considering a major rewrite for my memoir’s manuscript (and am looking forward to some feedback on the revised first chapter from a dear friend), and in the meantime, I’ve been reading. A lot.

The Love of the Samurai: A Thousand Years of Japanese Homosexuality, by Tsuneo Watanabe, with excerpts from the research of Jun’ichi Iwata.

日本男色物語 奈良時代の貴族から明治の文豪まで (Nihon Danshoku Monogatari: Nara-jidai no Kizoku kara Meiji no Bungō Made, The Story of Male-Male Love in Japan: From Nara Period Aristocrats to Meiji Literary Greats), by Makoto Takemitsu

Rereading Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan, by Gary Leupp

Rereading Tales of Idolized Boys: Male-Male Love in Medieval Japanese Buddhist Narratives, by Sachi Schmidt-Hori

Comrade Loves of the Samurai, by Saikaku Ihara (which is a 1928 translation of a 1927 translation (into French) of several of Ihara’s short stories, originally published privately but then re-released by Tuttle in the 1970s with a horrendously condescending foreword by a closeted professor desperate to avoid anyone thinking that he, too, was gay — too funny).

The Joy of Gay Sex, both the second edition, which I read in college, by Dr. Charles Silverstein and the late, lamented Edmund White, and the third edition, by Silverstein and the equally lamented Felice Picano.

男色大鏡 (Danshoku Ōkagami, The Great Mirror (or Encyclopedia) of Male-Male Love), by Saikaku Ihara (rewritten in modern Japanese by Masaharu Fuji). I also want to read the recent English translation by Paul Gordon-Schalow.

Queer as Folklore: The Hidden Queer History of Myths and Monsters, by Sacha Coward

With the exception of the Joy of Gay Sex books, my research is centered on pre-modern Japanese understandings of male-male love and sexuality. In addition to offering more insight for my memoir as I (may) revise it, I think there is a long essay waiting.

On several occasions during my decade in Japan, I was told either that the Japanese don’t understand homosexuality or, even more risible, that there were no homosexuals in Japan.

The last time I heard a variant of that latter remark, I was at a formal reception surrounded by Japanese politicians and bureaucrats, and could therefore not reply authentically without risking my then job. I did, however, replay that remark to several friends who all, bless them, shared my thought: If there are no homosexuals in Japan, then who the heck had I been schtupping for the past several years? (In the years before I met Hiro, I was, shall we say, an adventurous playmate for so many men that my neighbors, gratefully, assumed I was teaching private English lessons. Lessons they might have been, but I specialized in body language, if you get my drift, and I’m sure you do.)

That long essay, as I outline it, will review the different ways the Japanese language refers to both the modern notion of homosexuality, including in-group terminology (how gay Japanese men refer to themselves and others), and more academic language, including the use of Urning1 (Kraft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis (1886) was translated into Japanese in 1913 and Japan’s new crop of so-called sexologists — a pseudo-science akin to late nineteenth, early twentieth century fads like phrenology, the gender binary, and racial determinism — loved Urning before, in 1920, they settled on 同性愛 (dōseiai, same-sex love), the term that remains in academic and scientific use today.)

During the only eight years in Japan’s history when male-male sexuality was illegal (1873–1880), legal scholars invented a neologism, 鶏姦 (keikan, literally chicken mischief, don’t ask me why) to match the English2 term, sodomy. But the Japanese already had language to describe men who loved men.

Japan’s oldest historical records and poetry include references to Shintō priests and aristocratic men loving other men, and were usually described as intense friendships (but thankfully not roommates).

男色 (nanshoku, meaning the allure of men, a lust for men, or, literally, male colors) dates back to the eighth or ninth century, CE, from a second–century Tang Dynasty3 classic, The Book of Former Han. Nanshoku fell into use to describe a Buddhist practice, also introduced from China, whereby young male acolytes (age 14 to 21) from aristocratic families) were deeply (and sometimes contractually, to ensure mutual fidelity) loved by older monks until either the acolyte left the monastery or took the tonsure. From the twelfth century onward, however, it became a catch-all term for male-male relationships. Yukio Mishima wished to revive the linguistic use of nanshoku, too.

若衆道 (wakashūdō, the way (as in Tao, the Chinese philosophical term also imported into Japanese thinking) of young men, also abbreviated as 衆道 (shūdō), arose in the thirteenth century as samurai developed contractual relationships akin to Buddhist monks, whereby they formalized their love and devotion to young pages. But the use of contracts fell by the wayside as shūdō became more and more prevalent. Saikaku Ihara not only documents the devotion (and jealousy) of both samurai and their pages, revered for their beauty, but also how some of those relationships lasted for lifetimes. Shūdō was not limited to samurai, either, as both merchants and commoners in medieval Japan swooned for beautiful young men (and who can blame them — I recall Carl Van Vechten’s quip: “A thing of beauty is a boy forever.”)

Speaking of Ihara, he also coined a term (albeit a very misogynistic term) for men who never married a woman and remained in relationships with other men: 女嫌い (onnagirai, woman-hater), although, thankfully, that term never entered popular use.

陰間 (kagema, among the shadows) began as a seventeenth–century (early Edo period) description of Kabuki theatre4 apprentices. Apprentices, however, made very little money, and those with enough allure slept with both men and women fans to make ends (pardon the pun) meet. As the Edo period progressed, however, kagema was used to describe the men working in pleasure quarters, too. Japanese social commentators in the early twentieth century noted that the term had devolved to include the cheap, desperate male prostitutes working under the cover of dark amid the trees in the public parks of Japan’s largest cities, Tōkyō, Ōsaka, and Kyōto.

At no point in Japan’s history, therefore, had men who loved men not existed. The existence of bigots who wish we didn’t exist is a relatively new innovation in Japan, and one I hope will fade as quickly as most trends in Japan do.

Kraft-Ebing had read Plato’s Symposium, and in the Speech of Pausanias, Plato claimed that man’s love of men was inspired by Aphrodite Urania, the divine guise of love. From Urania, Kraft-Ebing crafted Urning.

Japan’s first attempt at a modern criminal code during the Meiji Restoration was influenced by legal scholars from Great Britain. Thankfully, French legal scholars brought news of the Napoleonic Code, and, in 1880, sodomy ceased to be a crime in Japan.

Japanese aristocrats in both the Nara and Heian periods loved, loved, loved all things Chinese and memorized both Tang Dynasty poems and literature as inspiration for their own writing.

Kabuki began as an all-woman theatre troupe, but authorities forced women off the stage, claiming that their beauty inspired violence in theatre-goers.