Is it Nostalgia?

Or is it Anger?

Hiro, my husband, and I attended my company’s annual holiday party last weekend. The event was wonderful (discounting the unskilled tarot reading I received): Hiro and I ate well and, better yet, we ran into many of the people I love to work with, coworkers and executives alike.

One room at the party was a dedicated arcade, with old pinball machines against the wall and, on the tables, some of the games I played as a kid: Battleship and Hungry, Hungry Hippos.

There was also a candy stand in that room, and before leaving the party, I went back to collect what I thought was an old favorite.

My uncertainty had little to do with the candy itself. The packaging has changed slightly since I was a kid, and I have long since conquered my lack of appreciation for licorice flavors—I tried salty licorice (made with an ammonium salt, not sodium chloride) from Iceland a decade ago and fell in love!

But Chuckles takes me back to a moment in my childhood where my emotions were very muddled and very dark.

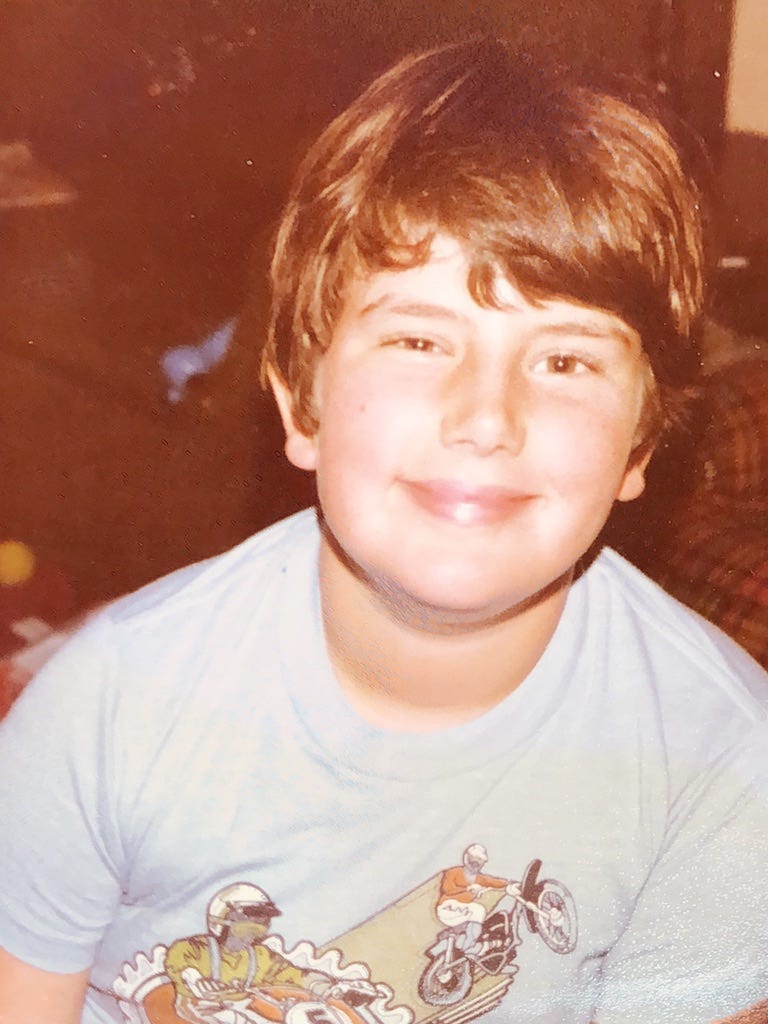

My father had his first heart attack in 1971. I was five, but more horrifically, my father was only 28. My mother tells me that the first doctor he saw, to complain about chest pains, dismissed him, saying my father only had a cold. Twenty-four hours and what must have been a long ambulance ride (we then lived in Orange County, New York, and my father was taken to Montefiore Hospital in Manhattan) later, the diagnosis came into focus, and my father underwent his first bypass surgery.

At the time, my father was an up-and-coming executive at a bank in the Bronx, Eastern Savings. He had been made a vice-president for a new area of expertise, data processing. (He showed my brother and me the massive computers he used one time, and his staff printed a large-format image of Snoopy—using only ones and zeroes—on a giant dot-matrix printer for us.)

But the heart attacks (and surgeries) kept coming.

To be closer to the city, my mother would drop us kids off at her parents’ home in Marycrest, a tiny community in Rockland County created by second-generation Irish employees of the Long Island Railroad, of whom my maternal grandfather was one.

I resented my maternal grandparents (my mother doted on me, but we were just another hassle for my grandparents, who had already raised eight children), and, even more so, I resented the weird uncertainty I inhabited. Why were my parents absent so much? What was going on?

But what about the Chuckles? I hear you ask.

My grandfather ran a candy store just inside the back door of the Marycrest house. (I remember him taking me to a wholesale store in Pearl River, where he did the unthinkably luxurious thing of buying whole boxes of candy—including Chuckles—to stock his store.) But it wasn’t really a store.

The back door opened onto the laundry room, and there was a chest of drawers along one of the walls. Atop the chest was a rack for the candy (alongside a tin, where candy buyers slipped their dimes for each purchase on the honor system), and the boxes of candy stock were kept in the drawers.

After my father’s first surgery, our entire family was asked to follow a low-cholesterol diet. Only skim milk—made from a powder—and no more butter, no more ice cream, no more chocolate.

My grandfather stocked a few chocolate items in his store, but I don’t remember being tempted by them. (There were Almond Joys and Mounds bars, but I didn’t learn to like coconut until later in life.)

The packs of Chuckles, however, were a different story. Plastic-wrapped sugar highs, each and every one, even if eating a pack meant finding a place to get rid of the licorice one.

Even if I had had spending money, I was told not to buy candy.

But do you know of any five-year-olds who can resist that level of blatant temptation? The candy was right there, in front of my face, every single day I was with my grandparents.

And so began my life of crime.

I deduced (being a bright little kid has its advantages, I suppose) that a theft would not be as noticeable if I stole from the stock boxes and not from the racks. On sunny days, I’d slip a pack of Chuckles into my corduroy pockets on my way out to ride my bicycle in Marycrest. (The licorice ones, together with the wrappers, were tossed deep into the woods or otherwise into the fields beyond my grandparents, out past the scary beehives and the vexsome chicken coop—because no, Grandpa, I don’t want to collect eggs this morning. You can’t make me! The chickens don’t like me!1)

I got away with my crime spree for several weeks. When my grandfather caught wise, he spanked me as he felt was necessary, but the beating doesn’t linger in my memory. I never had the sense that he liked me: he frequently rued that I wasn’t athletic like my brother, while telling my brother that he wished my brother were more academic, like me.

But I wonder now if the pro forma spanking (over his knee but with my corduroys still on) was a warped reflection of love for his first grandchild. He was mean to me, yes, but not as mean, according to my mother, as he was to his four daughters. Was the fact of my boyhood a saving grace, despite my lack of gross motor coordination?

I will say this, however. Two behaviors continued from my time in exile from my parents.

The (natural) inability to understand my emotions continued for decades past the point when young adults might normally suss them out. The resentment (and anger) I felt then only ceased to torture me (via my repression of those emotions) when I was twenty-five and finally (in the arms of a Japanese stranger) learned to let them out.

My criminal sneakiness stuck with me, too. I was a smooth and skilled liar during my teen years, a tactic necessary for life in the closet (even after the closet grew utterly transparent—my college friends nearly all knew I was gay before my official comings-out.

Let me end with a hint of good news. A brief excerpt from my manuscript, one that recalls the Japanese stranger I mentioned above, will be printed—in two parts—in January. I will, of course, include links when everything goes live.

The chickens never liked me, perhaps because I hadn’t learned to bring feed with me into the coop, and was therefore a target for pecking.